The True Story of ‘The Serpent and the Rainbow’

The impetus for the action in The Serpent and the Rainbow (1988) is the story of a man in Haiti who appears to be dead.

The Serpent and the Rainbow (1988) is a movie that has a split personality. For one, it’s a great horror movie directed by one of the masters of the genre, Wes Craven. The film has enough violence, supernatural happenings, and gory special effects to make it unmistakably a Wes Craven film.

The Serpent and the Rainbow isn’t just about scares though. More than that, it is a movie Wes Craven wanted to direct in a way that approached the subject of voodoo and zombies in a serious and balanced way. The Serpent and the Rainbow is horror, but it’s also a drama. It has scary people doing creepy things, but it also has political undertones that convey the unrest of its setting in Haiti. It is also based on a true story.

The “Real” Zombies of Haiti

The impetus for the action in The Serpent and the Rainbow (1988) is the story of a man in Haiti who appears to be dead. The man, Christophe Durand (Conrad Roberts), is checked by a doctor and declared dead. He is then buried, but years later Dr. Dennis Alan is sent to Haiti to track down Christophe who was recently discovered to be alive. As far-fetched as this story sounds, it is based in fact.

In May of 1962, a man named Clairvius Narcisse was declared dead by doctors at an American-directed hospital in Haiti. Narcisse had entered the hospital three days earlier with aches and a fever, but his illness could not be diagnosed. Seemingly dead, Clairvius Narcisse was buried. Nearly two decades later in 1980, Narcisse found his sister and told her he’d been dug up from his grave and forced to work on a sugar plantation.

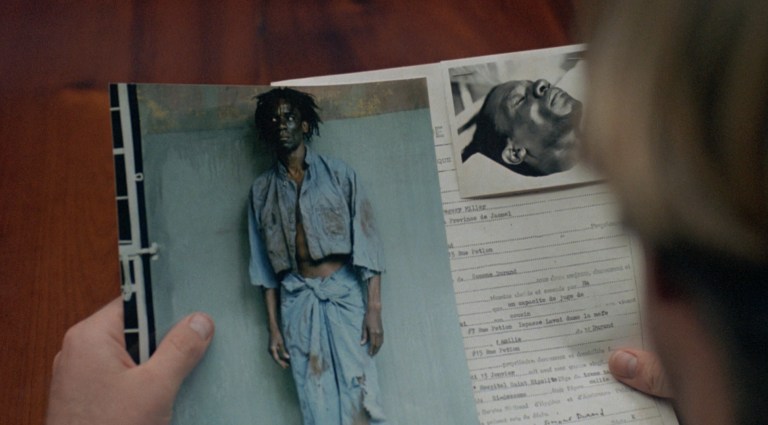

The character Christophe in The Serpent and the Rainbow is based on Clairvius Narcisse. The case of Narcisse is the most well-known and well-documented case of zombification, but it is not the only one. In 1988, a young man named Wilfred Doricent became gravely ill. He was checked by doctors, but eight days later he appeared to be dead. Doricent was buried, but days later he was no longer in his grave. Looking terrible and unable to speak, Doricent rejoined his family. His actions became erratic, and he appeared to have permanent brain damage.

Yet another example of zombification is that of Francina Ileus. Ileus’s case isn’t as well documented as some, but as the story goes, she was presumed dead in 1976 and buried. Rumors of her zombification began to spread, so police dug up her grave to dispel the stories, only to find her coffin empty. In 1979, a friend of Ileus came upon her while Ileus was wandering around in a catatonic state.

These are only three of the many cases of zombification in Haitian culture. Zombies may be a fringe part of the Haitian Vodou religion, but they are prevalent enough that they have even been recognized by the government. Though not named explicitly as “zombies,” the Haitian criminal code states that it is attempted murder to administer any substance that produces a “lethargic coma more or less prolonged,” and it is considered murder if that person is then buried, no matter if they escape the grave or not. This description appears to be a legal interpretation of the process of zombification explored in The Serpent and the Rainbow.

The Man Who Searched for a Zombie

Wes Craven’s The Serpent and the Rainbow begins, as many movies do, with a book. Published in 1985 was a book titled, in full, The Serpent and the Rainbow: A Harvard Scientist’s Astonishing Journey in the Secret Societies of Haitian Voodoo, Zombies, and Magic. The book is a personal account from anthropologist Wade Davis about his true experiences traveling to Haiti in the early 1980s in search of a “zombie poison.”

The poison in question is a powder that was said to kill a person and later revive them in a state where they are able to be mentally controlled by someone. As a scientist, Davis didn’t believe that such a thing could be done. But in 1982, colleagues of Davis informed him about Clairvius Narcisse’s apparent revival after being declared dead and buried years earlier.

Davis and his peers deduced that some sort of drug must be responsible for putting Narcisse into a state where enough bodily functions stopped so that he appeared to be dead, yet he was still alive. A drug like that could revolutionize anesthesia. Davis was then sent to Haiti to find the drug and bring it back to the United States, ostensibly for medical science, but, as Davis rather cynically relates in his book, for the money such a drug would make for whoever developed it.

Though the zombie powder was the reason for Davis’s trip to Haiti, he wanted his book The Serpent and the Rainbow to be a fair and illuminating look at a culture that was often misrepresented. Rather than capitalizing on sensationalistic stereotypes of voodoo and zombies, Davis says he “was trying to use the zombie phenomenon as a metaphor … about a society that I felt was being denigrated in a particularly racist way.”

Davis’s book is based in fact, but it reads somewhat like a thriller. Because of its unique approach to voodoo and its accessible style, The Serpent and the Rainbow became popular enough with general audiences for a movie studio to snatch the rights for an adaptation shortly after its release. At the time, Davis was hesitant about giving his book the Hollywood treatment. As he said in a contemporary interview, “I don’t like horror films, so obviously I was concerned.” In Davis’s own mind, a film similar to Peter Weir’s drama The Year of Living Dangerously (1982) would better represent his book than any horror film could.

Davis went back to Haiti and was on set while Wes Craven’s film adaptation of his work was being done. Bill Pullman, the star of The Serpent and the Rainbow, has said in his commentary on the movie that Davis’s input and assistance during filming was extremely important in how the film came together. Years later in a short documentary included on the home video version of the film, Davis says that Wes Craven’s movie makes a valiant attempt at portraying a side of Haitian Vodou not seen in other movies of its kind. Ultimately though, Davis thinks The Serpent in the Rainbow is a missed opportunity that fails to celebrate the religion as his book does.

Wes Craven’s Voodoo Masterpiece

Wes Craven fell in love with Wade Davis’s book and signed on to adapt it into a movie without even seeing a script. That was a bold move for the director whose well-documented lack of luck with studio interference had adversely affected his vision for his previous film, Deadly Friend (1986). Regardless, Craven was inspired by the idea of The Serpent and the Rainbow and worked to adapt the novel into a movie that he hoped would feel different from his previous work in horror.

Craven spent much of his career trying to shake the idea that he was just a horror director. In issue #70 of Fangoria magazine published prior to the film’s release, Craven describes The Serpent and the Rainbow as “an adult political thriller.” In fact, Craven did incorporate Haiti’s tumultuous political landscape into his movie by creating a character not present in Davis’s original book. The main antagonist of the film, Dargent Peytraud, is a representation of the unchecked government corruption in Haiti that led to multiple revolts.

The political landscape was also a part of daily life while making the movie. For the sake of authenticity, Craven began shooting The Serpent and the Rainbow on location in Haiti. At the time of shooting, Haiti was under a military rule that wasn’t any better than the autocratic dynasty that had been ousted the year before. The tension within Haiti could be felt by the cast and crew, and though the tension likely contributed to the intense feeling of the movie, it also contributed to the cast and crew being forced to leave Haiti and finish the shoot in the Dominican Republic.

For all the turmoil on the set of The Serpent and the Rainbow (and there was a lot of it), the finished movie does stand out for its approach to voodoo. Craven was an academic who was raised in a very strict religious household, and he loved approaching religion from various perspectives in his films. For The Serpent and the Rainbow, Craven stated in issue #71 of Fangoria that he wanted to present voodoo fairly and show the religion as “a well-rounded thing.” For this reason, Craven made sure to balance the more menacing elements of the movie with positive and uplifting elements.

Craven saw other voodoo movies of the time such as Angel Heart (1987) and The Believers (1987) as using voodoo simply as a threat. Those movies portrayed voodoo as a foreign and threatening. Ever since White Zombie (1932) introduced the idea of voodoo zombies to the United States, the vast majority of voodoo movies played into stereotypes that didn’t represent the full breadth of the religion. Craven sought more balance in his movie, and in many ways he achieved it.

In interviews conducted years after the release of The Serpent and the Rainbow, Wade Davis thinks studio pressure led to some of the more horrific and unrealistic scenes that dominate the later part of the movie. Craven had set out to make something other than horror, but in the end, it is a horror movie. It’s full of what Craven became known for in many of his early movies: frightening dream sequences, blood, and scenes of graphic violence. Craven may have had to comprise a bit in order to get the movie made, but he still made a wonderful film.

Haitian Vodou in ‘The Serpent and the Rainbow’

One of the most interesting things about The Serpent and the Rainbow is that it shows real Haitian Vodou ceremonies as they are taking place. Of course a lot of the people who practice the religion are quite secretive and not everything in the movie is real, but some of it is.

Early in the movie there is a scene where Bill Pullman’s character Dennis Alan is attending a dinner with Dr. Marielle Duchamp (Cathy Tyson) and Lucien Celine (Paul Winfield). During the scene, people are dancing and performing various voodoo rituals for tourists. In an interview on the movie’s Blu-ray, cinematographer John Lindley states that the person eating glass in the scene is using real glass and not a prop made to be chewed. Wade Davis goes even further and says the performers are not actors, they are people who are possessed. The glass eater, the man chewing burning embers, and the person allowing a tourist to push a needle through his cheek had all worked themselves into a trance according to their religion.

As for the zombification in the movie, though real people obviously weren’t made into zombies for the film, the process of making the zombie poison as shown by the character Mozart (Brent Jennings) is depicted closely to the way Davis describes it in his book. The main ingredient in the zombie powder is tetrodotoxin, a neurotoxin found in sea life including pufferfish. Tetrodotoxin is mentioned by name in The Serpent and the Rainbow, and a pufferfish is shown to be added with other authentic ingredients including a poison toad with a sea worm wrapped around it. However, some ingredients are made slightly more palatable for the movie. The book calls for the crushed skull of an infant who passed away a little more than a month prior, but the movie uses the rotted corpse of an old woman instead.

There was real voodoo behind the scenes as well. Craven stated in issue #71 of Fangoria that, in an effort to be respectful of the people in power in Haiti, he and producer David Ladd attended a voodoo ceremony meant to give the production protection from evil spirits. As Craven tells it, he and lad were taken to a field in the middle of the night where a pig was slaughtered in front of them. They were then approached with the expectation that Craven and Ladd would drink the pig’s blood, but the shocked looks on their faces let the two men off the hook.

On a mini-documentary on the Blu-ray, special effects artist David Anderson describes the cast and crew being taken by bus into the jungle. They entered a hut and were seated in preparation of a blessing ceremony. Rum was handed out to everyone, and the crew proceeded to get drunk while voodoo priests performed a ceremony involving music and dancing. Anderson recalls the dancers clearly becoming possessed “right before our very drunken eyes.” Unknown to Anderson at the time, he and his crewmates had sat through a protection ceremony very different from the one Craven and Ladd had experienced.

The story behind The Serpent and the Rainbow is just as fascinating as the movie itself. It is a story that is rich and extensive, and one that is difficult to condense into a single article.

For more stories about the making of The Serpent and the Rainbow only alluded to in this article (including an on-set revolt, crew members becoming possessed, and more about voodoo ceremonies behind the scenes), also be sure to check out Cursed Films II on Shudder, featuring new interviews with Wade Davis, Bill Pullman, and many other members of the film’s cast and crew. The second season of the weekly Shudder series explores movies including The Wizard of Oz (1939), Rosemary’s Baby (1968), Stalker (1979), Cannibal Holocaust (1980), and The Serpent and the Rainbow, telling tales of turbulent film shoots and mysterious happenings. And if you’re still in the mood for more voodoo after all that, check out Zombi Child (2019) on Shudder, another movie that involves the true story of Clairvius Narcisse.