Why Christopher Nolan’s 2014 Film ‘Interstellar’ Is Such A Sad Movie

A comprehensive analysis of the thematic and structural elements of Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar with introductory remarks on the place of sci-fi movies in the Western canon.

Table of Contents

Introduction

When I think of sci-fi cinema, particularly movies about outer space, the first thing that comes to my mind isn’t melodrama, sadness, or meditations on mortality. Instead, I envision fiery engines, advanced technology, killer lasers, steel — and a sense of violent propulsion and action-packed moments of a Marvel movie or some overly commercialized blockbuster.

Yet — when I push aside my impulsive first reaction to what a sci-fi movie is — it dawns on me that outer space is the perfect place for a sad movie to be set, and our culture is full of these references. David Bowie’s “Space Oddity” is a deeply emotional song. Kubrick’s 2001 A Space Odyssey is at its core more a melodramatic examination of the human condition than it is a movie about engines and robots.

And, I suppose, there are countless other examples. Because space — this infinite void, so oddly filled with spirited lights, energy sources, and spheres we call planets — is an ideal stage for examining the most pressing questions. Who created this thing? Where does the universe end? What is this place? Is anyone out there?

In our amnesic society, it might be surprising to realize that famous works such as Homer’s epics, Hebrew scriptures, and Dante’s Divine Comedy are essentially science fiction stories with astronaut-like protagonists. For the ancient Greeks, the vast and perilous ocean was as enigmatic and daunting as outer space is to us today. Homer famously referred to it as the “wine-dark sea.” The term “astronaut” has Greek origins, translating to “star navigator” or “sailor.”

The story of Moses leading the Israelites through vast and uninhabited deserts is another example. Their journey through the desert likely felt as alien and groundbreaking as space exploration did for NASA or Dr. David in 2001: A Space Odyssey. In the New Testament, Christ can be seen as the ultimate astronaut, embarking on a journey into the unknown depths of death and returning through the time-space continuum to his body, resurrected.

Dante’s Divine Comedy reaches its climax with the narrator finding himself in a gravity-free zone, observing planets and celestial spheres within the context of Ptolemaic astronomy—essentially floating in an ancient conception of outer space. In Canto XXII of Paradiso, Dante makes an observation that could just as easily have been uttered by a character in Interstellar: “And I saw this globe, so small, so lost in space…”

These are stories of strangers in strange lands, tales with their protagonists both metaphorically and literally exploring the outermost reaches of their known worlds. The mystery remains. From ancient Athens to modern Los Angeles, the only change is that our parameter of the unknown has become much wider.

And what do we find when we reach this transcendent threshold? When we venture to the place of zenith? When we strive to navigate the most challenging terrains in the most extreme ways? We discover an ideal setting for dramatic storytelling, where human experiences unfold in their most compelling and distilled forms.

I was thinking these thoughts as I re-watched Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar, experiencing the film again for the first time since I saw it in theaters in 2014. I couldn’t watch it as an action or sci-fi movie. It felt like a sad film about all the most thorny and vital aspects of being a human being.

My thoughts then drifted to Robert Zemeckis’s film Contact, which, superficially, revolves around space exploration and aliens, but on a deeper and more profound level, explores our individual potential and the ultimate purpose of the human species. Much like Interstellar, Contact is an incredibly moving film, with the crux of its drama rooted in human nature rather than technology or action sequences.

But don’t let me digress us with talk about Contact, one of my favorite films, and a film I would argue is probably one of the best movies ever made in all of history… The key point is that these so-called sci-fi, space exploration movies possess immense dramatic pathos. These films are epic statements on the human condition.

So let’s get into the way Interstellar sings as a movie in so many beautiful ways. We’ll focus on a variety of concepts all of which connect to the inherent sadness of the film.

Homesickness

With Interstellar, Christopher Nolan highlights the profound loneliness of space.

Watching the movie, I found myself thinking about my own travel around the world and times I felt homesick while in some far corner of the world, uh, that unsettling sensation of being discombobulated, yearning for familiar surroundings and familiar faces but being helplessly marooned somewhere with none of your common creature comforts, nothing familiar but perhaps the memory of familiarity, which actually just makes the pang all the more intense.

Yet what is homesickness when you are in fact still on Earth? The only homesickness I know is one while still on my home planet, merely a day away from the solace of my bed, the presence of my family, and the stability of my everyday life.

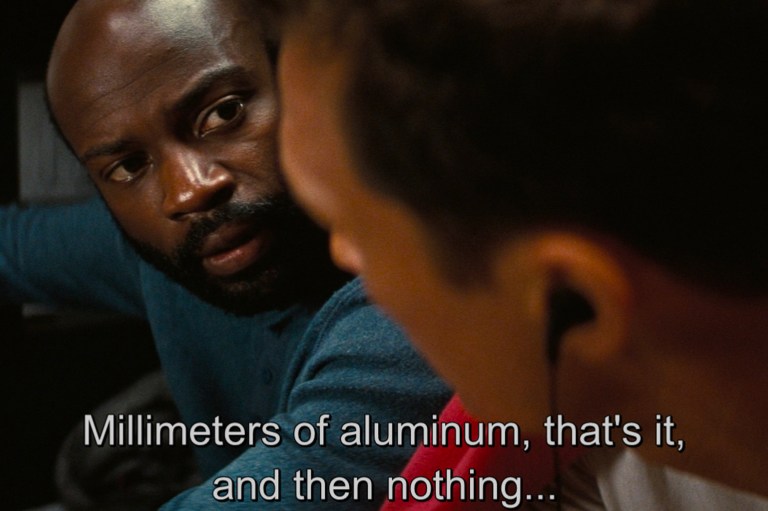

The above thoughts occurred to me during the point in the film where the crew had finished there two-year journey to Saturn. Just imagine how you would feel if you were two years away from home. Nolan’s screenplay here does a perfect job of making us consider that through David Gyasi’s character, Romily, who is breaking down and mentally and says: “It gets to me. This tin can. Radiation, vacuum outside — everything wants us dead. We’re just not supposed to be here.” And yet they can’t turn back.

And the vast emptiness of space does indeed exacerbate matters, I suppose, if you were two years from home, and with family, or had something familiar to hold onto, that might make it bearable. But for the crew in Interstellar there are just infinite horizons of isolation stacking on each other, infinitely. As I watched their tiny spaceship fly by Saturn in the darkness, I realized how quickly I would succumb to madness in that ship. Stuck in a small confined environment, with no privacy, years away from home? An impossible ask; I couldn’t do it. This realization deepened my admiration for the characters and the pain of the journey, as well as the real-life explorers who have ventured into space or foreign lands throughout history, and those living in exile.

The Gift of Earth

Nolan’s meditation on homesickness is made more painful through the screenplay’s constant reminder of how special Earth was.

Some posit the observable universe is 109.368 trillion times larger than the width of Asia. That is to say — it would take you 20.8 trillion years to cover the entire observable universe at a constant speed of 3,000 miles per hour. This is the setting and background for Interstellar.

Within this virtually infinte setting, the fictional scientists of Project Lazarus can only pinpoint 12 potentially habitable planets. Remarkably, out of these 12 planets, only 3 hold any real promise as livable. Earth is a celestial oasis, and Nolan’s screenplay reminds us of this fact, evoking both a sense of melancholy and a call for stewardship.

The moment that truly captured the gift of Earth for me was when the characters landed on Miller’s Planet. Initially, Nolan lulls the audience into a sense of familiarity, making it seem as if they had landed above something akin to the Pacific Ocean. However, he quickly pulls the rug out from under us — this is not an ocean like ours, but an inhospitable expanse of shallow water plagued by gigantic tsunamis.

Who are we to be bored by the beauty of a mountain, even a hill? Even an insect crawling on a blade of grass? A lake; a bear; even the logical beauty of a paved road, running through a bustling town. I think of a poem by Milosz that I think of all the time:”We suffered and this poor earth was not enough.”

But poetics aside, truly, isn’t that the point of Miller’s Planet? This deep philosophical reminder: even if Earth only had one single beach, and not even a pristine Caribbean one at that, it would still make it one of the most beautiful places in a place to big to even track by mileage. We suffered and this poor earth was not enough.

A Loneliness Beyond Loneliness

I believe Nolan’s screenplay then intentionally amplifies the concept of homesickness for our beautiful planet into a profound sense of loneliness that can only be described as a transcendent — a loneliness beyond loneliness.

Hell is often described as other people, yet this statement reveals a privilege held by those fortunate enough to be surrounded by others. We only like being alone in the context of having been with other people.

Stripe all people from our lives and we aren’t so much alone, as we are alone. Not, really, living a life of solitude, but stripped of life all together. How can you even be human, live a life, if there is no one else there to confirm the chain of your existence?

This a loneliness beyond loneliness, something perhaps worse than death, because at least with death you might be able to say it is an off button fully pressed, but this kind of loneliness turns everything off without taking you offline.

A loneliness beyond loneliness permeates the entirety of the film. Yet is most violently expressed when Dr. Mann, played by Matt Damon, awakens from cryosleep and exclaims, “Pray you never learn just how good it can be to see another face.” I don’t think many people can fathom the depths of loneliness one must plunge to say something like that.

A Politics of Innovation

On a more positive yet still sad note, Interstellar embraces a certain optimism on human nature, celebrating the characters’ heroic resourcefulness. This optimism, though, is tinged, as the innovative spirit propelling them requires significant sacrifices.

Interstellar’s Socio-Political Setting

When I first watched Interstellar in 2014, I didn’t realize it was a film about environmental collapse. It also went over my head that the story takes place in a world where the US government fabricates conspiracies to discourage innovation. Cooper’s character is outraged that textbooks claim the moon landing was a hoax designed to bankrupt the Soviet Union. The deception’s purpose is to keep children focused on growing food, rather than dreaming big or thinking ambitiously.

As Cooper reflects on the current state of affairs while sipping a beer, he notes:

We’ve always defined ourselves by the ability to overcome the impossible. And we count these moments. These moments when we dare to aim higher, to break barriers, to reach for the stars, to make the unknown known. We count these moments as our proudest achievements. But we lost all that. Or perhaps we’ve just forgotten that we are still pioneers. And we’ve barely begun. And that our greatest accomplishments cannot be behind us, that our destiny lies above us.

Joseph Cooper

Interstellar’s pathos derives a great deal from the fact that the film doesn’t linger on Earth’s demise. Cooper simply states, “Mankind was born on Earth. It was never meant to die here.” With that, the entire crew sets to work to address the crisis. This aspect isn’t inherently sad; in fact, it serves as an inspiring, if somewhat idealistic, model. It also enhances the characters’ appeal. Instead of posturing, they selflessly sacrifice themselves.

A Tangent on Political Feasibility

By almost all accounts, Contact is a more melancholic film than Interstellar. Nolan’s film is preposterous and fantastical, to the point it can feel like a superhero movie at times, especially with the happy ending.

This is one aspect that makes Contact a more poignant film poignant in comparison to Interstellar. In Contact, the primary obstacles and the elements that stymie us are governmental bureaucracy, the military-industrial complex, sensational media coverage, and the public’s fanatical reactions. In Interstellar, the characters magically overcome all of this without any real struggle, whereas Contact ends on a note of failure, or at the very least an optimism poisoned with despair.

Nolan’s Ethical Tapestry

In Interstellar, there’s a major theme of balancing duty to family with duty to the whole human race. While other films deal with this struggle, Interstellar stands out because it stacks multiple moral problems on top of each other like a set of Russian nesting dolls.

Cooper, is torn between saving his daughter or saving humanity. He’s caught in the difficult choice of either ensuring his family’s safety or serving the collective good.

His daughter, Murph, faces her own moral bind as she deals with her trauma bond: “Do I harbor resentment for my father, or do I make the most out of my difficult life?” She must negotiate the friction between resentment and adventure.

Tom, Cooper’s son, is confronted with the focused question: “Do I cater to my family’s immediate needs or acknowledge the looming doom of humanity?”

Professor Brand is ensnared in a Faustian predicament: “Do I sacrifice my integrity to save humanity?” His choice lies between revealing the mission’s true purpose and its slim chances of success, or tricking the crew to ensure they remain committed to humanity’s salvation.

Dr. Amelia Brand, played by Anne Hathaway, grapples with a dilemma of science versus a quasi-religious conviction: “Do I follow my heart or uphold the mission?” She is split between her personal connection to a colleague on a potentially habitable planet and following the scientific data.

Interstellar skillfully threads these ethical conundrums into a moral tapestry, allowing the movie to resonate not just as entertainment, but as a guiding compass for life’s dilemmas.

The Pathos of Aging

Aging is a difficult topic to illuminate in cinema. Movies are often too short to cover the horror and beauty of the passing of time on our bodies in a satisfying or realistic way. Interstellar has one genius scene that does a pretty darn good job though.

The crew goes on a mission to a planet near a supermassive black hole named Gargantua. Due to the extreme gravitational forces of Gargantua, time on this planet is dilated; one hour on the planet is equivalent to seven years outside its gravitational influence. Three crew members head to the planet. One crew member stays behind.

Nolan makes the time the crew spends on the planet extremely dramatic and intense. One character on the mission dies and does not return with them. It’s probably the most action-packed sequence in the entire film. As a viewer, you feel incredibly anxious, not just because of the rapid intensity of the scene, but also on emotional level because you know that every hour they spend there, they are losing so much time with their loved ones. The sacrifice is palpable.

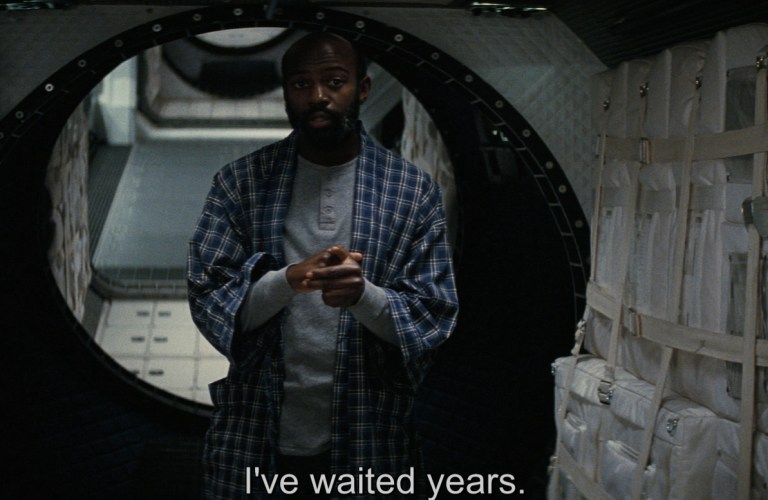

Barely escaping death, once they get off the planet, the viewer’s heart rate goes down. Finally, they are safe, and enough time has not passed for all of their friends and family to be dead. Yet, Nolan artfully delivers another emotional punch, as while all this was going on, we had forgotten about the other crew member left behind on the spaceship.

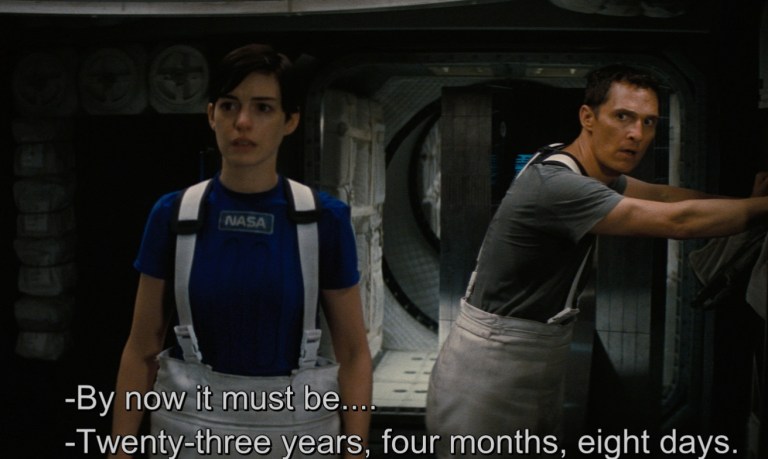

When the door opens, and the crew returns to the safety of their ship, the crew member that stayed behind says holding back tears in his eyes and his beard noticeably grayer than when we last saw him — “I’ve waited 23 years for you.” It’s a devasting moment and one of the most beautiful portrayals of the inherent sadness of passing in time in movie history.

Cooper and Amelia watch all the video signals from Earth sent by their family over the past two decades. They confront the reality of their decision to venture into space and realize the significant moments of life they have missed. Cooper’s children age from adolescents to adults in the messages. His son shares updates on his life, including both tragic and joyful moments. Meanwhile, Murph only sends one message on her birthday, reminding Cooper of his past words:

Today’s my birthday. And it’s a special one because you once told me…You once told me that when you came back we might be the same age… and today I’m the age you were when you left.

Murphy Cooper

The Visceral Pain of Death

Before revisiting Interstellar, my most vivid memory from watching the film was the emotionally-charged ending sequence. I vaguely recalled McConaughey’s character being trapped in the tesseract or stranded within the infinite bookshelf, and ultimately reuniting with his daughter on her deathbed. It’s probably the most famous scene from the movie. Coming back to this scene nearly ten years later, the poignancy struck me more intensely.

I think everyone that has seen Interstellar is most fixated on the relationship between Cooper and his daughter, Murph. It’s the crux of the screenplay and the emotional journey of plot is all designed to lead us to the final scene when Cooper and Murph are reunited.

Cooper has aged only a few years while Murphy is in her late 90s or early 100s. Surrounded by her children and grandchildren, whom Cooper has never met due to his mission. I suppose the best answer is the stark contrast between the father’s youth and the daughter’s age highlights the immense time that has been lost between them.

At first blush, it seems like a such a surreal trick that it should feel cheesy, yet Nolan somehow makes it work. And, however surreal, it smacks you in the face with a certain paradoxical reality of time — before it begins, it has somehow ended.

The Sadness of Responsibility

With all of this a larger point is threaded by Nolan’s screenplay, and it’s a certain sadness that pervades all aspects of the heroic element of the film. We can refer to it as the morbid nature of our responsibility to the planet, to our family, and to humankind. Here are the main takeaways.

- Love — while real — does not guarantee happiness. The love between Copper and Murphy is as real as it gets. It transcends time and space. Yet they never had much time together or shared a life of joy with each other.

- There is never enough time for love. Copper and Murph had a relationship that required such an ultimate sacrifice, and now with the mission complete, they can’t enjoy the fruits of their labor. It’s too late.

- The inevitability of death always supersedes any resolution. While Copper and Murphy saved the world, they won’t be able to experience the joy from it.

- We aren’t here for ourselves, but for future generations. The grandchildren being there subtly sinks in the theme of the movie. Cooper was told his daughter would die on earth from environmental collapse, but by the end of the movie they have the left planet and a new generation is emerging thanks to their work.