How Stranger Things Evoked an Era Through Easter Eggs

The series is stuffed with Easter eggs: deep-cut references that reward those who are in the know.

The upcoming fifth season of Stranger Things, delayed by the Hollywood strikes, will supposedly be the end of the line for the Netflix series.

All good things must come to an end, and Stranger Things has already grown well beyond its origin as the buzziest show of summer 2016. It’s rejuvenated veteran actors’ careers, produced breakout stars from multiple generations, and defined a new retro aesthetic that isn’t so much about recreating an era as evoking the feelings associated with it.

The Duffer Brothers’ series is also stuffed with Easter eggs: deep-cut references that reward those who are in the know. A complete guide could fill a book (and needless to say there’s a wiki), but let’s break them down by category.

All grown up

From the beginning, the series bought credibility and congratulated those in the know about its ’80s setting by casting actors who were popular at the time. Some of those actors were just kids in the Reagan era, and now play parental figures. Their elders, now in the mad-scientist demographic, are back too.

The greatest casting coup was top-billed Winona Ryder, iconic star of cult classics like Beetlejuice (1988), Heathers (1988), and Edward Scissorhands (1998). When Stranger Things premiered, she played the frantic mom of missing Will Byers and his older brother Jonathan. Season one also starred Matthew Modine, in the ’80s a twentysomething star of movies like Vision Quest (1984) and Full Metal Jacket (1987), as the villainous Dr. Brenner.

In later seasons, those actors were joined by Goonies (1985) star Sean Astin, Aliens (1986) company man Paul Reiser, and Princess Bride (1987) hunk Cary Elwes. The show also boosted its ’80s pedigree, in a manner of speaking, by casting Maya Hawke — whose mom Uma Thurman played an ingenue in Dangerous Liaisons (1988) and whose dad Ethan Hawke was a child star in Explorers (1985).

The tropes

“Read any Stephen King?” asks Becky Ives in season one, trying to explain the abilities her sister Terry attributed to her daughter, known to viewers as Eleven. That author’s books and movie adaptations — including Carrie (1976), Firestarter (1984), and Stand By Me (1986) — are among the inspirations for Stranger Things plot points.

The popular culture of the 1980s, when Stranger Things is set, provides numerous touchstones for the show’s stories. Some of the connections are explicit and in-universe, as in the way Dungeons & Dragons becomes a metaphor for the kids to make sense of their quest to rescue Will. Some of them are left for us to spot, like the way electricity provides a conduit to the supernatural (see: 1982’s Poltergeist) or the way the adventuring kids evoke The Goonies (1985).

What makes the Stranger Things approach distinctive, and gives the show such appeal for viewers younger than its gen-X characters, is the way the Duffer Brothers make these tropes their own. Steven Spielberg’s E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982), for example, is a master reference for season one — but the Duffer Brothers splice it with Stephen King to give the material a darker thrill.

The quintessential moment comes in episode seven, when government agents block the kids’ bikes. E.T. lifted his young friends’ bikes into ecstatic flight, but Eleven instead lifts the adults into the air, dropping their van upside-down onto the pavement in a way that presumably kills everyone inside. Pointedly, she doesn’t look back.

Style points

Every detail of the show’s style is curated to evoke the early home video era, when VHS was still battling it out with Betamax and paperbacks with lurid covers captivated kids in supermarket aisles. The show’s opening credits evoke the typography of Stephen King novels, with the episodes given “chapter” numbers to underline the literary reference. Imaginary Forces, the studio that digitally created the titles, deliberately added so many analog-like glitches that people who actually designed titles in the ’80s said such visible errors would never have been acceptable.

The filmmakers were able to be more authentic to the era with the characters’ fashions: instead of using leg warmers and giant bangs to scream “1980s!”, costume designer Amy Parris lavished care on specific details sourced from actual high school yearbooks. She even took the setting into consideration: kids in a small Midwestern town like Hawkins wouldn’t be keeping up with Studio 54. When Eleven and Max went mall shopping in season three, it gave Parris and her team a chance to showcase some fresher fashions.

The show’s interior rooms are also filled with a profusion of period detail. There are obvious signposts like movie posters (The Thing, The Dark Crystal), but whereas a less thorough production might stop there, Stranger Things fills its spaces with details like Hopper’s discarded Hamm’s can, Nancy’s “God’s eye” yarn craft, and multicolored Venetian blinds as seen in…that’s right, E.T.

The sounds of a generation

With Netflix money behind Stranger Things, music supervisor Nora Felder was able to snag some of the period’s most popular songs. The Police’s “Every Breath You Take,” Toto’s “Africa,” and Cyndi Lauper’s “Time After Time” all figured in season one alone.

Some of the song choices are subtler: for example, seasons one and three both feature a symphonic cover of David Bowie’s “Heroes” by Peter Gabriel. While the track doesn’t exactly fit the setting — the original came out in 1977, and the cover was released in 2010 — both Bowie and Gabriel were MTV icons, so the recording resonates.

Felder’s greatest coup, though, was “Running Up That Hill.” The show staked a lot on the 1985 Kate Bush song, which was central to the plot of season four. It paid off big time, with the timelessly eerie track becoming a top-ten hit and forcing DJs to explain why a 37-year-old art pop song was getting played alongside Harry Styles and Jack Harlow.

Composers Kyle Dixon and Michael Stein are responsible for the Stranger Things score, striking just the right balance between terrifying and tender. No actual ’80s score sounded quite like the Stranger Things music: a more orchestral sound was still common, although synthesizers were a staple of the horror genre. What matters is that the music fits our idea of what the ’80s should sound like, a sense shaped by pop music (see: Kate Bush and her burbling synth lines) more than by film scores.

Out of the mouths of babes

“Lando Calrissian!” cries Dustin in season one, when Lucas argues the kids should trust Chief Hopper. His point: you never know which of your seeming friends has secretly made a deal with the bad guys.

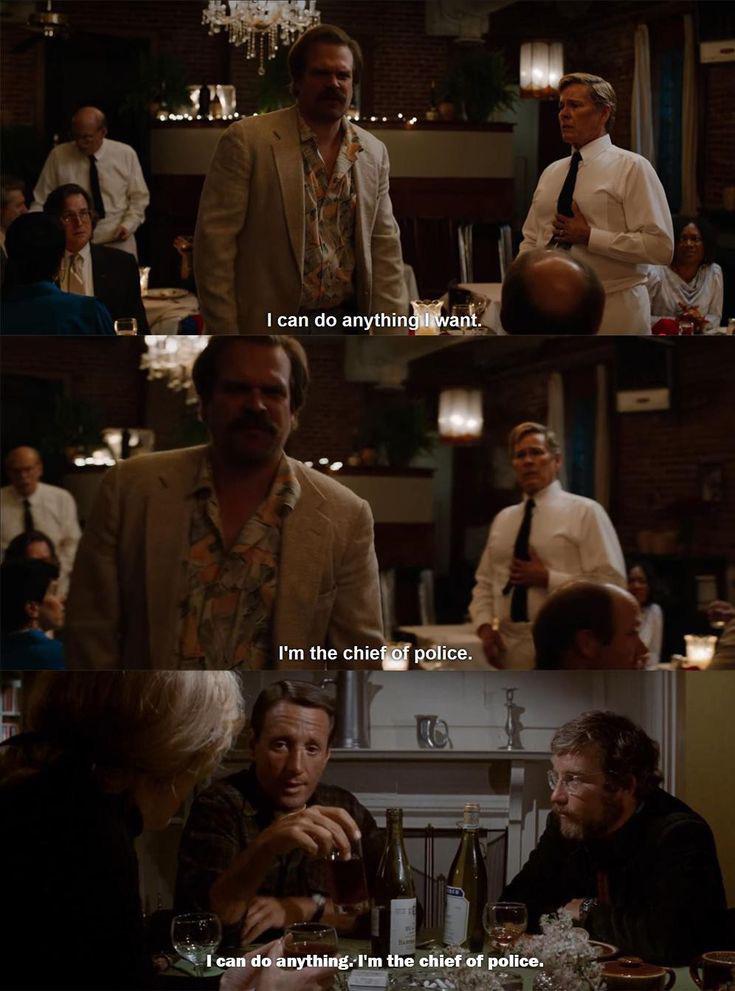

It’s one of dozens of moments where the show’s dialogue illustrates the characters’ contemporary pop culture references. Steve sings Bob Seger’s “Old Time Rock and Roll,” Hopper quotes a line from 1975’s Jaws (“I’m the chief of police. I can do anything”), and Max swoons over Ralph Macchio from 1984’s The Karate Kid (“I bet he’s an amazing kisser”).

Of course, the show isn’t above a little anachronism when it’s called for. One of Argyle’s most memorable lines in season four — “Hold onto your butts, brochachos!” — anticipates Samuel L. Jackson in Jurassic Park (1993). Ultimately good advice, like good TV, is timeless.

Further reading: