Is ‘The Skulls’ (2000) Based on a True Story?

The Skulls is a memorable early 2000s thriller both because of its teen stars and because it was based on a salacious open secret.

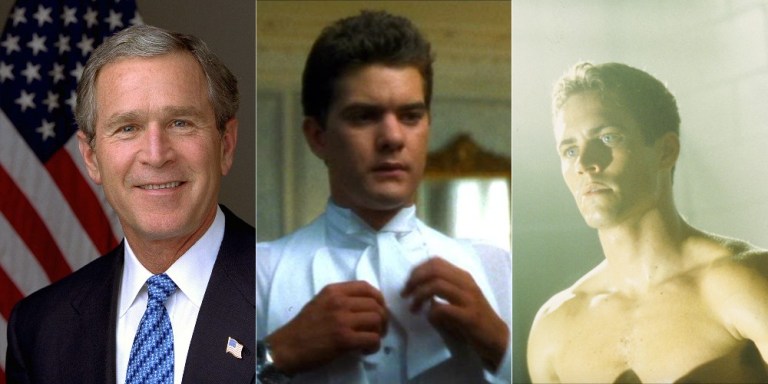

The Skulls starring Joshua Jackson, Paul Walker and Leslie Bibb is a memorable early 2000s thriller both because of its teen stars and because it was based on a salacious open secret: there really is a secret society at Yale called “Skull and Bones” and if you look up their list of alumni you’ll find former presidents, judges, diplomats and owners of major media outlets.

The plot of The Skulls follows Luke McNamara (Jackson), a working class orphan and junior at a prestigious (unnamed) Ivy League school he attends on a rowing scholarship. To the displeasure of his friends Chloe (Bibb) and Will (Hill Harper), Luke is invited to join the most prestigious secret society at the school, The Skulls. Upon initiation he is given wealthy heir Caleb Mandrake (Walker) as his partner.

If it’s secret and elite, it can’t be good.

Will Beckford, The Skulls

Tensions arise when Luke’s friend Will is killed while investigating The Skulls for an expose in the school paper and his death is framed as a suicide. Luke is suspicious, but Caleb tries to convince him that he needs The Skulls to fund his dream of going to law school more than he needs to uncover the truth about Will. However, Luke keeps investigating and eventually the secret society turns on him and seeks to eliminate him as a threat to their secrecy.

While Luke McNamara and Caleb Mandrake are completely fictional characters, writer John Pogue went to Yale and director Rob Cohen went to Harvard and the story is absolutely meant to portray real aspects of how elite secret societies function. At the time, it was also especially relevant as then-president George W. Bush was an alumnus of the real Skull and Bones secret society at Yale. John Kerry, who ran for president in 2004, is also an alumnus.

What is the real Skull and Bones?

It was a very intense set because I had in my mind that I was telling the story of George Senior and George W Bush. I had gone to Harvard that had the dining clubs but not the skull and bones, the secret societies. But I knew a lot about the secret societies, and I thought this is how the elite functions. This is how the elite knits together these bonds that take them through life and keep them in the elite heights of any society, and I was very excited about portraying that with Paul and Josh and all the cast. To create this secret world of power elites… that was very exciting to me and I got the cast excited about that idea. It’s interesting how many of the critics missed this and didn’t understand it and blowed it off as silly. Skull and bones is a reality and the film got very close to how that reality works at Yale.

Rob Cohen on “The Skulls”

In each Yale class, only 15 students are selected for lifetime membership in the secret society that has been around since 1832. This makes it Yale’s oldest secret society. Members are called “Bonesmen” and must swear loyalty to the club and its members for life. There are around 800 Bonesmen alive today and the purpose of the club is to keep it’s members in the elite areas of society.

The first example of this goal is the fact that one of the club’s founder’s son became a Bonesman at Yale and went on to become the only man to serve as both Supreme Court Chief Justice and president, William Taft. George W. Bush was admitted to Yale despite poor schoolwork in high school by a committee which included three Bonesman. Later, when George W. Bush was elected president in 2000, he brought on 5 other Bonesman into his cabinet.

The society’s headquarters is called “The Tomb” and is located at 64 High St. in New Haven. It has almost no windows and an iron door secured by padlocks. Reportedly, inside the building are prized Skull and Bones “artifacts” like the skull of indigenous leader Geronimo, whose family unsuccessfully sued to be allowed to respectfully rebury the body of their ancestor. George W. Bush’s paternal grandfather, Prescott Bush, is rumored to be responsible for stealing Geronimo’s skull as he worked at Fort Sill and was known for stealing for the club.

I think Skull and Bones has had slightly more success than the mafia in the sense that the leaders of the five families are all doing 100 years in jail, and the leaders of the Skull and Bones families are doing four and eight years in the White House

Ron Rosenbaum, Skull and Bones

The club was the second-to-last at Yale to start accepting women. It happened only after pushback from about half of its alumni (the vote was 368-320 in favor of accepting women) who felt that if women were allowed into The Tomb, they would be raped by Skull and Bones members. The implication being that not only are Bonesmen rapists, but that this group of members would rather their club be full of rapists than women. They were so passionate about this that alumni showed up and changed the locks on The Tomb the year they started inviting women. When the club simply met elsewhere, alumni sued.

George W. Bush’s Yale classmate Ron Rosenbaum has been investigating the Skull and Bones for three decades. He was initially just interested in the strange building the members occupied on campus, remembering that “during the initiation rites, you could hear strange cries and whispers coming from the Skull and Bones tomb.” Yale graduate Alexandra Robbins wrote the book Secrets of the Tomb: Skull and Bones, the Ivy League, and the Hidden Paths of Power about the secret society and says most members she contacted hung up on her or harassed and threatened her.

My senior year I joined Skull and Bones, a secret society, so secret I can’t say anything more.

George W. Bush, A Charge to Keep

How does a secret society keep its secrets?

One thing The Skulls got right (we think) is that Bonesmen are required to give part of their estate to the society in their will. There is also an annual fundraising request sent to members. This allows the society to ensure all members are “financially secure for life” in order to protect themselves from someone selling the club’s secrets. New members are said to receive cash gifts of $15,000 after completing initiation.

The Russell Trust Association was created as the business arm of the secret society, though that entity reported less than $4 million in assets to the IRS in 2016. Skull and Bones also owns Deer Island in New York which is a 40-acre retreat for members.

Skull and bones is a reality and the film got very close to how that reality works at Yale.

Director Rob Cohen on “The Skulls”

Supposedly, as The Skulls was released in 2000 members received a letter warning them to remain silent. This may have worked. While audiences liked the film, critics hated The Skulls and its two sequels, The Skulls II (2002) and The Skulls III (2004), went straight to video.