‘A Clockwork Orange’ (1971) Film: Detailed Analysis

The Meaning of Stanely Kubrick’s a Clockwork Orange | Sex, Ultraviolence, and the Great War Between Free Will and Social Responsibility.

A Clockwork Orange is a stupendously violent 1971 crime film by Stanley Kubrick that stands as one of the most controversial films ever made.

Its graphic violence and repeated depictions of rape led to a string of copycat crimes in England that caused Kubrick to pull it from distribution in the UK until his death. Despite being slapped with an “X” rating (the precursor to NC-17), the film was nominated for several Academy Awards, including Best Picture.

Using music and imagery that is both disturbing and otherworldly, the film builds upon the 1962 Anthony Burgess novel of the same name. Although critics and scholars have argued over the film’s meaning for years, A Clockwork Orange quite clearly attempts to be a critique on juvenile delinquency, the psychiatric profession, governmental overreach, and—most importantly—the eternal struggle between free will and social responsibility.

Original Trailer

There is no dialogue or narration in this minute-long trailer. Instead, it features a sped-up, synthesized version of The William Tell Overture as images from the film flash by the eyes as quickly as a strobe light while words intermittently appear such as “WITTY … FUNNY … SATIRIC … MUSICAL … EXCITING … BIZARRE … POLITICAL … THRILLING … FRIGHTENING … METAPHORICAL … COMIC … SARDONIC … BEETHOVEN … ” What’s notable is how many of these words involve the idea that the film was satirical and not to be taken seriously.

Movie Summary/Plot

A Clockwork Orange is narrated by the main character, Alex (Malcolm McDowell), a youth gang leader in a dystopian England that may or not be set in the near-future. Alex is the incarnation of unrestrained male id—that is, until his underlings and the legal system decide to put him in check.

The film starts off with Alex and his “droogs”—a word derived from a Russian word basically meaning “friends”—drinking drugged-up milk at a local bar to get themselves in the mood for some “ultraviolence” as well as “the old in-out, in-out” (sexual intercourse).

The four gang members are shown mercilessly thrashing a drunken old homeless man who begs them for spare change. Then they enter an abandoned warehouse and interrupt a gang rape led by rival leader “Billyboy” to engage in a full-scale rumble that Alex and his droogs easily win. They are then shown joyriding out to the countryside in a car they’ve stolen. They ring the doorbell of a country house, and when the lady of the house lets them in, they proceed to violently rape her while their husband, whom they’ve beaten into permanent disability, is forced to watch. During the rape, Alex sings verses from the classic movie song “Singin’ in the Rain.”

The next morning, Alex is visited at home by his probation officer, a sleazy-looking fellow named PR Deltoid, who warns him that he’s being watched and should curtail his sociopathic activities.

As time grinds on, Alex’s overbearing personality alienates the other gang members, who plot on staging a coup. The intra-gang tension is exacerbated one day while the boys are walking along a council block and Alex suddenly tosses two of his droogs into the river and slices one their hands using a long knife.

Having had enough of Alex, his droogs wait outside while Alex invades the house of an older woman who collects cats. Alex rapes her so brutally, she dies from her injuries. While escaping through the house’s front door, Alex is smashed in the head with a milk bottle by Dim, the biggest and dumbest of his droogs, causing Alex to be disabled long enough for the police to catch and arrest him. Alex is convicted of murder and sent to prison.

Alex is a model prisoner for two years, although he busies himself with fantasies of being a Roman Centurion whipping Jesus Christ en route to the crucifixion and other sick daydreams that suggest prison has not changed him internally.

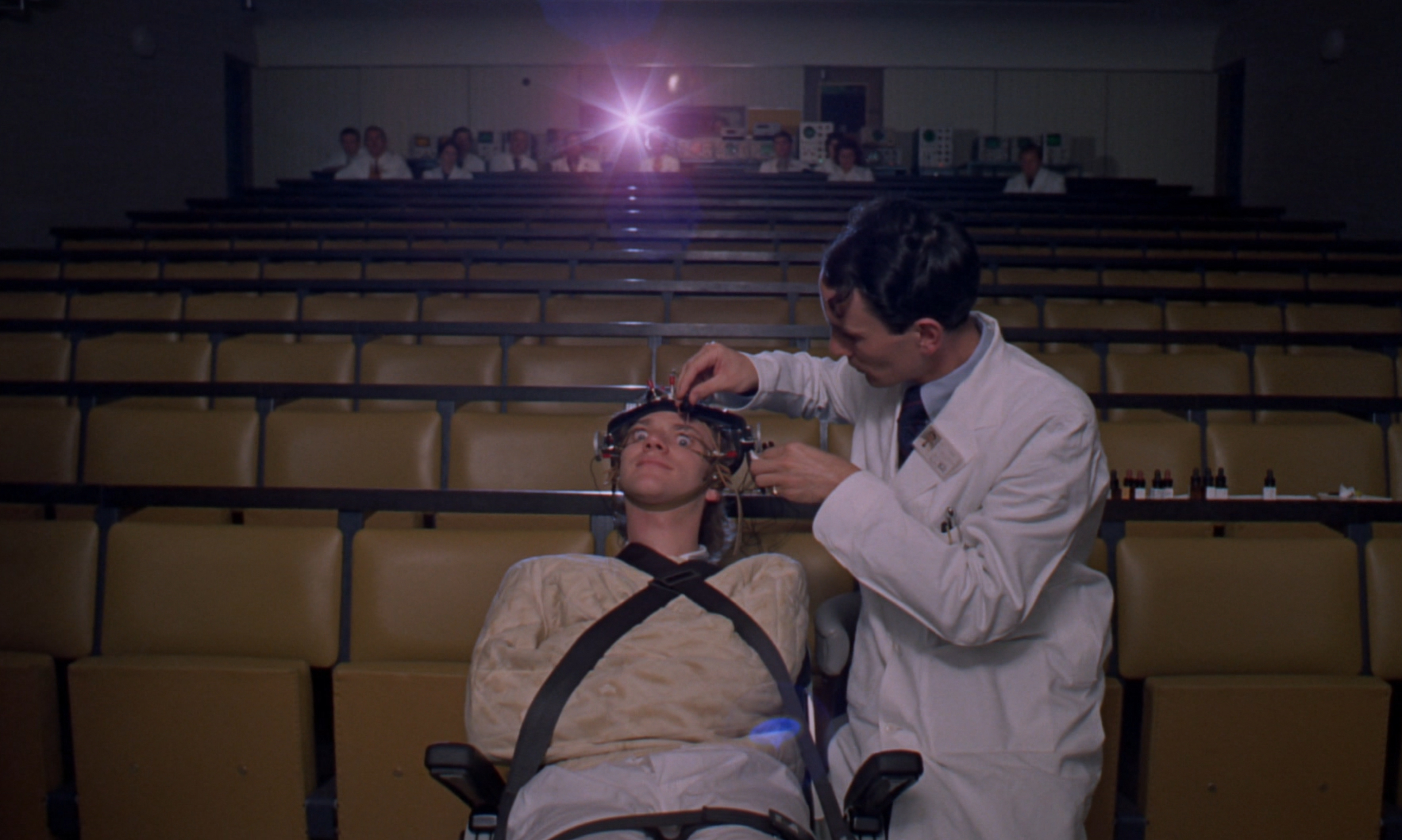

Then one day he is approached by a government official who offers him freedom from prison if he consents to being an experimental guinea pig for what is known as the “Ludovico Technique”—an experimental Pavlovian treatment wherein Alex is injected with a serum and then forced to watch imagery and footage of extreme sex and violence. The treatment’s goal is to induce nausea in Alex whenever he is tempted to rape or assault someone. Perhaps unintentionally, the physicians also play music from Alex’s favorite composer, Ludwig Van Beethoven, during the treatment, which also makes Alex become sick whenever he hears Beethoven’s music.

The prison chaplain vigorously opposes the treatment, arguing that for free will to have any meaning, it must be voluntary, but Alex was having his free will stripped from him as a result of the Ludovico Technique.

A few weeks after the treatment, Alex is dragged out on stage for the pleasure of the government’s Interior Minister and other onlookers. A man comes up to Alex and starts verbally and physically abusing him. When Alex feeling tempted to fight back, he becomes intensely nauseous. Instead of fighting back, he licks the sole of the man’s shoe as commanded. Then a gorgeous topless woman in panties is presented to Alex, who is still on his knees after being humiliated by the abusive man. Alex briefly attempts to grab her breasts, only to be overcome with waves of sickness again.

The Ludovico Technique is declared a success, and Alex is released from prison. He attempts to go and live with his parents again but is coldly informed that they’ve found another lodger—a young man who doesn’t make a habit of getting in trouble with the law.

Roaming the streets alone and homeless, Alex again encounters the old man that his gang beat up at the film’s beginning. The man suddenly realizes who Alex is and joins other homeless people in administering Alex a gang beating.

Two policemen encounter Alex—but they are Georgie and Dim, two of his former droogs, who drag him out to an open field and almost drown him in a trough filled with dirty water.

Desperate for help, Alex rings the doorbell of a nearby country house, unaware it’s the same house where he and his droogs raped a woman and crippled her husband. At first, the husband, now in a wheelchair, notices Alex from the newspaper headlines about his controversial “rehabilitation.” The man invites Alex into his house. But while Alex, still recovering from his multiple beatings, starts absentmindedly singing more verses from “Singin’ in the Rain” in the man’s bathtub, the man realizes to his horror that this is the gang leader who raped his wife and rendered him permanently dependent on a wheelchair.

Furious to the point of madness, the man locks Alex in an upstairs room and blasts Beethoven’s music through giant speakers aimed at the ceiling. Driven insane by the music, Alex jumps out the window and nearly dies in a suicide attempt.

Humiliated by how the Ludovico Technique has backfired, the Interior Minister promises to reverse the technique’s effects and promises Alex a job in his new governmental administration. As newspaper reporters gather around Alex’s hospital bed, he poses for happy photo ops with the Interior Minister. Inside his head, he’s fantasizing about having vigorous sex with a naked woman as a group of upper-crust British socialites surround them and applaud. In a voiceover by Alex, the film’s final line is, “I was cured, all right.”

Film Analysis/Themes

The film’s main theme can be distilled down to the age-old question of whether two wrongs make a right—or, in other words, whether the ends justify the means no matter how unethical the means may be. In short, is it good to do bad things to someone, to strip away their humanity and free will, so long as that person stops doing bad things to others?

The Ludovico Technique was successful in getting Alex to stop attacking and raping people. But it backfired in the sense that it wound up rendering him defenseless against multiple attacks. It wound up driving him to attempt suicide.

On a production call sheet, Kubrick described the film thusly: “It is a story of the dubious redemption of a teenage delinquent by condition-reflex therapy. It is, at the same time, a running lecture on free-will.”

In an essay shortly after the film’s release, Stanley Kubrick described A Clockwork Orange as “A social satire dealing with the question of whether behavioural psychology and psychological conditioning are dangerous new weapons for a totalitarian government to use to impose vast controls on its citizens and turn them into little more than robots.”

Not everyone was impressed with A Clockwork Orange. Film critic Pauline Kael chided Kubrick for sexually exploiting the film’s female victims. Writing in the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert said:

Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange is an ideological mess, a paranoid right-wing fantasy masquerading as an Orwellian warning. It pretends to oppose the police state and forced mind control, but all it really does is celebrate the nastiness of its hero, Alex.…Alex is the sort of fearsomely strange person we’ve all run across a few times in our lives – usually when he and we were children, and he was less inclined to conceal his hobbies. He must have been the kind of kid who tore off the wings of flies and ate ants just because that was so disgusting.

Cast of A Clockwork Orange

Malcolm McDowell: Alex

The narrator of, and the main character in, both the novel and the film. Alex is a violent teenaged sociopath who loves Beethoven, “ultraviolence,” and rape. He leads a gang of “droogs” (roughly, “buddies” or “homeboys”) through increasingly chaotic adventures but becomes so overbearing, they eventually turn on him.

After viewing McDowell in If…. (1968), Kubrick decided that only McDowell could play Alex. He later said that if he couldn’t sign McDowell on for the role, he probably would have shelved the whole project.

When offered the role, McDowell originally thought that the director was Stanley Kramer, which made him reluctant to take the part. But when he learned that it was Stanley Kubrick, director of 2001: A Space Odyssey, he eagerly jumped onboard. At 27 years old when the film began shooting, McDowell was ten years older than the character he was playing in the film.

James Marcus: Georgie

Georgie is the oldest member of the gang and essentially the second in command. When he starts to resent Alex’s bullying of the other gang members, he begins plotting a takeover.

Warren Clarke: Dim

“Dim” is thus named because he’s not very bright. But he is valued in the gang because of his brawn and fighting ability. He always carries a chain with him wherever he goes. Dim is the droog who smashes a milk bottle in Alex’s face after the murder of the cat lady, temporarily disabling Alex and enabling the police to capture him. Toward the end of the film, he and Georgie have reinvented themselves as policemen and beat the “rehabilitated” Alex within an inch of his life.

Michael Tarn: Pete

The youngest member of Alex’s gang, Pete is also the quietest and most obedient. It is unclear what happens to him at the end of the film, as he is never seen again after the “cat lady” scene that ends with Alex in prison.

“It is inappropriate to talk about the characters in A Clockwork Orange as heroes and villains. The film is satire. You don’t have to make Frank Capra movies to like people. Capra presents a view of life as we all wish it really were. But I think you can still present a darker picture of life without disliking the human race. And I think Frank Capra movies are wonderful. And I wish life were like most any one of them. And I wish everybody were like Jimmy Stewart. But they’re not.”

—Stanley Kubrick, when asked by film critic Gene Siskel if Alex was a villain

Patrick Magee: Mr. Alexander

The veteran character actor portrays an author who lives in a modernistic countryside house along with his wife until the night when Alex and his droogs show up and force him to watch as they rape his wife. They also give him a beating that confines him to a wheelchair for the rest of his life. Then, much later in the film, when a beaten-up Alex shows up at Alexander’s house begging for mercy, he recognizes Alex from all the news about his criminal case. But when Alex starts singing verses of “Singin’ in the Rain” while in the bathtub, Alexander is driven mad with anger and sets it up so that Alex attempts to commit suicide.

More Characters/Analysis

- Adrienne Corri: Mrs. Alexander — Corri only appears briefly at the beginning of the film when she naively opens the door at her country estate. In walk Alex and his droogs and proceed to rape her while Alex belts out “Singin’ in the Rain” and forces her husband to watch.

- Paul Farrell: Tramp — Farrell portrays the acoholic, panhandling homeless man that Alex and his droogs savagely beat during one of the opening scenes. Then, much later in the film, he spots Alex—who, due to the Ludovico Technique, is no longer able to defend himself—and severely beats him along with several of his homeless friends.

- Sheila Raynor: Mum— Alex’s deeply ineffectual, compliant, and perpetually intimidated mother.

- Philip Stone: Dad — Alex’s equally milquetoast father. Both of Alex’s parents are helpless to do anything about their son’s out-of-control behavior.

- Clive Francis: Lodger — The proxy “good son” who moves into Alex’s room when he’s in prison. When Alex returns from incarceration hoping to move back into his room, he is informed that he’s been replaced by a young man who won’t cause them any trouble.

- Miriam Karlin: Cat Lady — The eccentric woman whose mansion houses countless cats as well as pop art paintings and a giant phallic sculpture. She dies as the result of Alex’s violent rape, which lands Alex in prison.

- Aubrey Morris: PR Deltoid — Alex’s smarmy, oily, and possibly pedophilic probation officer.

- Anthony Sharp: Minister of the Interior —The government agent who seeks to win public favor and votes by introducing the Ludovico Technique to Alex.

- “The Minister, played by Anthony Sharp, is clearly a figure of the Right. The writer, Patrick Magee, is a lunatic of the Left… They differ only in their dogma. Their means and ends are hardly distinguishable.” —Stanley Kubrick

- Michael Bates: Chief Guard Barnes — An over-the-top law-and-order type who mercilessly grills and belittles Alex during his prison journey. Chief Guard Barnes is a British version of Gunnery Sergeant Hartman in Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket (1987).

- Godfrey Quigley: Prison Chaplain —An empathetic counselor to Alex who decries the negative effects of the Ludovico Technique. Kubrick said that the Chaplain was the most ethical character in the entire film.

“The Minister, played by Anthony Sharp, is clearly a figure of the Right. The writer, Patrick Magee, is a lunatic of the Left… They differ only in their dogma. Their means and ends are hardly distinguishable.”

—Stanley Kubrick

A Clockwork Orange‘s Ending Explained

What does Alex mean when he says he was “cured”? Upon a cursory glance, it seems to mean that he was back to having free will, which most would agree is a good thing. But the fantasy of having sex with a woman while people watch and applaud would also suggest that Alex would continue with his rapacious and murderous ways, which most would agree was a bad thing.

Alex is a complex character. Most viewers are repelled at the violent, remorseless gang leader, although they’d also admit that he’s charismatic. But many viewers, seeing as how he became an experimental guinea pig for the state, which rendered him even more vulnerable than most of his victims, would also view him with some sympathy.

The most sensible explanation for the ending is that although Alex was “cured” of the Ludovico Technique’s ill effects, the film’s actual villain is the government, which holds a monopoly on the ability to abuse and is thus incurable.

“The government eventually resorts to the employment of the cruelest and most violent members of the society to control everyone else — not an altogether new or untried idea. In this sense, Alex’s last line, ‘I was cured all right,’ might be seen in the same light as Dr. Strangelove’s exit line, ‘Mein Fuehrer, I can walk.’ The final images of Alex as the spoon-fed child of a corrupt, totalitarian society, and Strangelove’s rebirth after his miraculous recovery from a crippling disease, seem to work well both dramatically and as expressions of an idea.”

—Stanley Kubrick

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a “droog”? In fact, what is the almost incomprehensible language that Alex and his gang speak?

| appy polly loggies | apologies |

| bolshy | big, great |

| chelloveck | person, man, fellow |

| cutter | money |

| devotchka | young woman |

| droog | friend |

| eggiweg | egg |

| fashed | bothered, annoyed, tired |

| horrorshow | good, well, wonderful, excellent |

| in-out in-out, the old in and out | sexual intercourse |

| luscious glory | hair |

| malchick | boy |

| moloko | milk |

| Moloko plus | milk laced with drugs |

| tolchock | push, hit |

| viddy | see |

| yarbles, yarblockos | testicles |

Do they get drunk off milk in the movie? What is that about?

Why was the film banned in the United Kingdom?

“Stanley was mesmerized by the language of the book. Not for one moment did I think, ‘Oh my God, there will be trouble.’ The film didn’t show any true cruelty….We had press in front of our house, we started receiving horrible letters, and then came the detailed death threats. The police said: ‘I think you would be better off leaving the country.’ Then we were really alarmed. So Stanley phoned Warner Bros. and begged to have the film withdrawn. He was right to do it.”

—Christiane Kubrick, Stanley’s widow

Why was the film rated “X”?

Startlingly, the first three years after the new ratings system came into effect, two “X”-rated films were nominated for Best Picture at the Academy Awards. The first, Midnight Cowboy (1969) actually won Best Picture despite earning an “X” rating for its shocking depictions of homosexual prostitution and violent depravity in Manhattan. A Clockwork Orange originally received an “X” rating due to its “ultraviolence” and a few very graphic (if brief) sexual scenes. In 1972, Kubrick edited about 30 seconds of sexual content from his film and re-released it in the USA with an “R” rating to gain wider distribution.

Is A Clockwork Orange disturbing?

How did they do the eyeball scene?

What does the title A Clockwork Orange mean?

In a 1972 television interview, he said, “Well, the title has a very different meaning but only to a particular generation of London Cockneys. It’s a phrase which I heard many years ago and so fell in love with, I wanted to use it, the title of the book. But the phrase itself I did not make up. The phrase ‘as queer as a clockwork orange’ is good old East London slang and it didn’t seem to me necessary to explain it. Now, obviously, I have to give it an extra meaning. I’ve implied an extra dimension. I’ve implied the junction of the organic, the lively, the sweet – in other words, life, the orange – and the mechanical, the cold, the disciplined. I’ve brought them together in this kind of oxymoron, this sour-sweet word.”

In essence, the Ludovico Technique had rendered Alex to be half-human (orange) and half genetically modified machine (clockwork). Many linguists disagree with Burgess’s claims of repeatedly hearing this phrase in London, arguing that no printed evidence exists prior to the publication of Burgess’s novel that it was a slang term at all. In a completely alternate explanation, they insist Burgess made up the story about overhearing it. Instead, they say the original title was A Clockwork Orang, with “orang” being a Malay word meaning “man,” and that the original title meant to convey the idea of a mechanical man. They say that Burgess was overcompensating for the fact that the book’s publisher made a huge typo, thinking that Orang was a misspelling.

If the story is set in the future, why does it still resemble the 1970s?

“Clockwork Orange is a satirical study of life as it was in 1960, when the tone of postwar England was socialistic, collectivist, and I was really trying to satirize that sort of world in which people had nothing to live for, had no energy–except for the young, who could do nothing with their energy but employ it to totally barbarous ends. I was really writing about the present. The then present. The now past. The future is already in the past. In Clockwork Orange, I had world telecasts and men on the moon. Of course, these things have come true; but there’s nothing in the book that wasn’t already present in the technology of the early Sixties, except for the use of a composite dialect called Nadsat.”

Did Alex ever have consensual sex with women, or was he purely a rapist?

What is Alex’s surname (last name)?

Although Dim and Georgie obviously became police, what happened to the other droog, Pete?

What about deleted scenes?

- The droogs encountering and assaulting a librarian, just as it occurred in the novel. The scene was deleted after Billy Russell, the actor who played the librarian, died.

- The gang stealing the sports car that they were later seen taking a joyride in.

- Alex pouring himself some milk at the Korova bar by pinching the naked statue’s nipple.

- Alex taking the girls he met at the record shop for a meal at a place called the Pasta Parlour.

- After having sex in his room, Alex and the two girls he met at the record store attempt to flee the house when Alex’s father comes home, only to be caught.

- The gang plying a group of old ladies with food and drinks to give them an alibi for when they go out to commit more crimes.

- The gang trashing a train car that they are riding home.

- The gang staring at the stars and contemplating life after a long night of ultraviolence.

What about rumors that Malcolm McDowell almost drowned in the scene where Dim and Georgie “waterboard” him by repeatedly dunking his head in a water-filled trough?

What are some popular culture references to the movie?

- The 1972 David Bowie song “Suffragette City” contains the line, “Say droogie, don’t crash here!”

- A 1973 episode of British comedy series The Goodies called “Invasion of the Moon Creatures” features Bill and Tim dressing up like droogs from the film A Clockwork Carrot and going on a rampage of rape and violence.

- When Malcolm McDowell hosted an episode of the first season of Saturday Night Live in 1975, he did an ad for the “American Milk Association” in character as Alex.

- In the 1997 film Batman & Robin, a motorcycle gang dresses like Alex and his droogs.

- In the 2008 film The Dark Knight, Heath Ledger says that his rendering of The Joker was inspired by Alex DeLarge.

- The Carl Showalter character in Fargo (1996) says he’s looking for ‘the old in-out in-out.”

- In the video for the song “Tattooed in Reverse,” Marilyn Manson appears in costume as Alex DeLarge.

- The violently reckless character Spike in the TV series Buffy the Vampire Slayer has a chip implanted in his brain that causes him pain whenever he gets violent. The producers say that this notion was inspired by A Clockwork Orange.

- The Simpsons has made repeated references to A Clockwork Orange.

- Lana Del Rey has a song called “Ultraviolence” and references the movie explicitly in unreleased track called “Hundred Dollar Bill”.

Trivia + Facts

- Anthony Burgess originally sold the film rights to Mick Jagger, lead singer of The Rolling Stones, for a mere $500. The original plans were to star Jagger as Alex and the rest of the Stones as his droogs. The band’s manager, Andrew Loog Oldham, even wrote the liner notes to a Stones album in Nadsat, the language used in A Clockwork Orange. But then the project was shelved, and Jagger resold the film rights.

- For a time, Ken Russell, a master of bombast who probably would have filmed a version equal to Kubrick’s in terms of controversy, was named as director. Russell planned to cast Oliver Reed as Alex.

- Terry Southern, who worked with Kubrick on Doctor Strangelove, originally suggested to Kubrick that Burgess’s book would make a great film. Southern had planned to cast Mod icon David Hemmings as Alex.

- Burgess, who was never happy with the film’s ending, wrote and produced a 1987 stage play called A Clockwork Orange: A Play With Music.

- During a costume fitting for his droog outfit, Malcolm McDowell came into the room dressed in a white shirt and his protective athletic cup. Kubrick suggested that the cup be placed on the outside of McDowell’s pants, and thus a new distinctive gang codpiece style was born.

- In the scene where Alex is abused by the actor who forces him to lick the bottom of his shoe, Malcolm McDowell had been kicked so hard that he accidentally broke a rib and suffered a blood clot.

- Malcolm McDowell is able to burp on cue. This is one of the many reasons Stanley Kubrick hired him for the part.

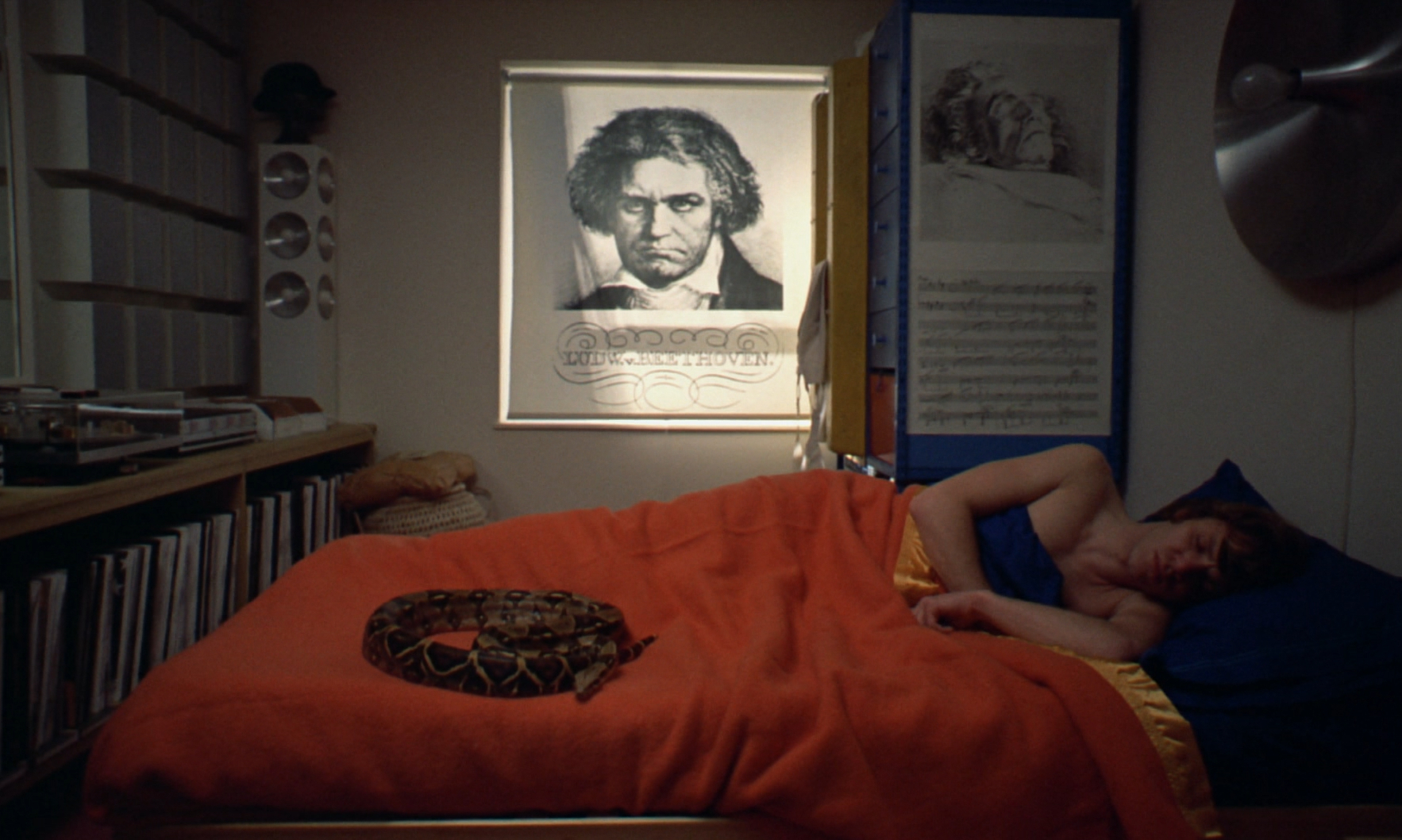

- When Kubrick was informed that McDowell had a morbid fear of snakes, he introduced Alex’s pet snake “Basil” into the plot.

- The sped-up sex scene in Alex’s bedroom with the two girls he met at the record shop clocked in at 28 minutes at regular speed.

- Malcolm McDowell once encountered actor/dancer Gene Kelly at a party. Kelly, incensed at how he felt McDowell had tainted the legacy of his trademark song “Singin’ in the Rain,” reportedly walked away in disgust without saying hello.

- Several album covers can be spotted in the record-shop scene: the soundtrack to Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, Pink Floyd’s Atom Heart Mother, Tim Buckley’s Lorca, Rare Bird’s As Your Mind Flies By, CSN&Y’s Déjà Vu, John Fahey’s The Transfiguration of Billy Joe Death, The Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour, Neil Young’s After the Gold Rush, and Mungo Jerry’s In the Summertime.

- Macolm McDowell, who reportedly had a very good working relationship with Kubrick during the filming, felt snubbed by the fact that Kubrick never contacted or interacted with him again after filming was done.

- Filming the rape of Mrs. Alexander proved to be so taxing for the original actress hired for the role that she quit. She was replaced by Adrienne Corri, who reportedly joked to Malcolm McDowell that he would get to see that she is a “natural redhead.”

- A year after the film’s release, electronic musician Walter Carlos had gender-reassignment surgery and had his named changed to Wendy Carlos.

- A Clockwork Orange is the only Kubrick film where Kubrick wrote the entire screenplay.

- Kubrick originally wanted Italian composer Ennio Morricone to score the film, but Morricone was busy with other soundtrack projects.

- The film was released less than a year after principal photography began, making it the fastest film that Kubrick ever shot, edited, and released.

- David Prowse, the musclebound actor who played Julian, Mr. Alexander’s caregiver, would go on to wear the Darth Vader outfit in the original Star Wars trilogy.

Soundtrack/Music

A Clockwork Orange turned a whole new generation onto classical music, which in the early 1970s was considered unhip and boring by the younger generations. By linking artists such as Beethoven and Rossini to sex and violence, Kubrick suddenly made classical music seem dangerous and exciting. The film’s official soundtrack was released in 1972 by Warner Brothers and contains the following tracks:

- “Title Music from A Clockwork Orange” (From Henry Purcell’s “Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary”)

Composers: Wendy Carlos, Rachel Elkind

Performed by: Wendy Carlos

Length: 2:21

This music is heard throughout the film: during the opening titles; right after the opening rape scene; when the topless girl comes onstage to tempt Alex during the exhibition of the Ludovico Technique’s effect on him; and when his former droogs, now rehabilitated as policemen, attack him after his release from prison. - “The Thieving Magpie (Abridged)”

Composer: Gioachino Rossini

A Deutsche Grammophon Recording (Rome Opera House Orchestra conducted by Tullio Serafin, 1963, uncredited)

Length: 5:57

This plays during the original rumble in the abandoned warehouse between Alex’s and Billyboy’s gangs; when Alex tosses Dim and Georgie into the water; and when the gang breaks into the cat lady’s house. - “Theme from A Clockwork Orange (Beethovian)”

Composers: Wendy Carlos, Rachel Elkind

Performed by: Wendy Carlos

Length: 1:44 - “Ninth Symphony, Second Movement (Abridged)”

Composer: Ludwig van Beethoven

A Deutsche Grammophon Recording (Berlin Philharmonic conducted by Ferenc Fricsay, 1958, uncredited)

Length: 3:48

This is played during the scene where Alex is in his bedroom and experiences transcendently violent bliss while listening to Beethoven’s music. - “March from A Clockwork Orange (Ninth Symphony, Fourth Movement, Abridged)”

Composers: Ludwig van Beethoven, Friedrich Schiller (lyrics)

Performed by: Wendy Carlos

(Articulations: Rachel Elkind)

Length: 7:00

An electronic version of Beethoven’s 9th symphony is heard during the scene at the music store when Alex is talking with the two girls and also when the Ludovico Technique is being performed upon Alex. - “William Tell Overture (Abridged)”

Composer: Giaochino Rossini

Performed by: Wendy Carlos

Length: 1:17

A sped-up electronic version plays during the scene where Alex is having sex in his bedroom with the two girls from the record store. An orchestral version is played when Alex returns from prison and his parents tell him that his room has been rented out to a lodger. - “Pomp and Circumstance March No. I”

Composer: Edward Elgar

Performed by: Marcus Dods (uncredited)

Length: 4:28

This music is played when England’s Minister of the Interior visits Alex’s prison. - “Pomp and Circumstance March No. IV (Abridged)”

Composer: Edward Elgar

Performed by: Marcus Dods (uncredited)

Length: 1:33

This march plays when Alex is shepherded from the prison to the facility where the Ludovico Technique is performed on him. - “Timesteps (Excerpt)”

Composer: Wendy Carlos

Performed by: Wendy Carlos

Length: 4:13 - “Overture to the Sun” (rerecorded instrumental from Sound of Sunforest, 1970)

Composer: Terry Tucker

Performed by: Terry Tucker

Length: 1:40 - “I Want to Marry a Lighthouse Keeper” (rerecorded song from Sound of Sunforest, 1970; film version differs from soundtrack version)

Composer: Erika Eigen

Performed by: Erika Eigen

Length: 1:00

This quirky novelty song is heard when Alex returns to his parents, only to be rebuffed by them. - “William Tell Overture (Abridged)”

Composer: Giaochino Rossini

A Deutsche Grammophon Recording (Rome Opera House Orchestra conducted by Tullio Serafin, 1963, uncredited)

Length: 2:58 - “Suicide Scherzo (Ninth Symphony, Second Movement, Abridged)”

Composer: Ludwig Van Beethoven

Performed by: Wendy Carlos

Length: 3:07

Mr. Alexander sets up giant speakers to play this song at maximum volume while Alex is locked in a room upstairs, forcing him to jump out the window and almost kill himself to escape the music that the Ludovico Technique has made him unable to hear without extreme physical and emotional distress. - Ninth Symphony, Fourth Movement (Abridged)”

Composer: Ludwig van Beethoven

A Deutsche Grammophon Recording (Berlin Philharmonic conducted by Herbert von Karajan, 1963, uncredited)

Length: 1:34

This is played at the end of the film after Alex’s “cure” when newspaper reporters come to visit him at the hospital. - “Singin’ in the Rain” (recording taken from the soundtrack of the 1952 film)

Composers: Arthur Freed (lyrics), Nacio Herb Brown (music)

Performed by: Gene Kelly

Length: 2:36

Alex sings an a cappella version of this famous song during the rape of Mrs. Alexander. The original version is played in its entirety as the ending credits roll.

Anthony Burgess Novel

The 1962 novel A Clockwork Orange was written by British author Anthony Burgess. Although it would become, by far, the book Burgess was most well-known for, he considered it one of his inferior works. He says he wrote it in one long gallop over a three-week period where he was for some reason gripped with the delusion that he was dying from a brain tumor.

Burgess had spent some time in Malaysia during World War II, but when he returned home to London, his wife was violently raped by four American soldiers, a traumatic experience that formed the kernel of this book, as several scenes feature women being raped, the most notable of which is the rape of Mrs. Alexander, who is raped by Alex and his three friends while they beat her husband—an author—into being permanently disabled.

Some minor differences between the book and the film are that the girl that Billyboy’s gang rapes, as well as the two girls that Alex picks up in the record store, are all depicted as about 10 years old in the book, while they are all sexually mature in the movie. Alex is also 15 at the book’s beginning and 17 when it ends. In the movie, he is depicted as a couple years older. Also, Alex’s gang beats up a librarian rather than a homeless man in the beginning, although, like the homeless man, the librarian gets their revenge at the end.

The major difference between the original English version of the book and the movie—and it’s a huge one—is that American publishers omitted Burgess’s 21st chapter, in which Alex sees the error of his ways and decides to live a righteous life. American publishers didn’t like that ending and preferred that the book end on a darker note. Kubrick based his film on the American version of the book.

This proved to be Burgess’s main objection to the film. He was raised a strict Catholic, and he felt that the final chapter was necessary to prove that once a man is given free will—or, rather, after his free will is restored subsequent to being rendered a mechanical animal by a totalitarian government’s medical experiment—it is up to him to choose good.

Movies Similar To A Clockwork Orange

- Vinyl (1965) is a 70-minute black-and-white film by Andy Warhol that is based on the Anthony Burgess novel A Clockwork Orange, but with names and locations changed.

- If…. (1968) stars Malcolm McDowell as the leader of a gang of lower-class boys at a British boarding school who plan to upend the school’s oppressive social structure. Stanley Kubrick was so impressed with McDowell’s performance that he decided only McDowell could play Alex in A Clockwork Orange.

- Romper Stomper (1992) stars Russell Crowe as the leader of a racist skinhead gang in Australia who attempt to fight against increasing waves of nonwhite immigrants. Some of the fight scenes are disturbingly realistic.

- Fight Club (1999) Brad Pitt and Edward Norton star in the cinematic adaptation of Chuck Pahlaniuk’s novel about male violence.

- American Psycho (2000) Christian Bale portrays Patrick Bateman, a status-obsessed yuppie serial killer, in this adaptation of the Bret Easton Ellis novel.

- Joker (2019) Joaquin Phoenix won an Oscar for Best Actor in Todd Phillips’s film about a bullied loner who finds redemption through savagely retaliatory acts of violence.

A Clockwork Orange Streaming

Where can you stream A Clockwork Orange? HBO Max has the streaming rights at the moment for the full movie. Click here to stream it there. You can also rent it on Amazon Prime. That said, the best way to experience the movie is through physical media. As of this writing, the 4k Blu Ray disk is $20.45 on Amazon Prime.