Alfred Hitchcock’s ‘Psycho’ — The First Modern Horror Film

Uncover all there is to known about the first modern horror film, “Psycho”, made by no other than the iconic filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock.

Analysis

By 1960, Alfred Hitchcock was one of the world’s most famous and respected film directors. He was also one of the few people in American history, before or since, to be universally recognized merely for being a director. Despite all this, Paramount Pictures wanted nothing to do with his planned adaptation of the 1959 Robert Bloch novel Psycho, finding it to be “too repulsive.”

Being a stubborn creative sort with a dogged faith in his own vision, Hitchcock persisted anyway, using his TV film crew and paying his actors unusually low wages to produce the 1960 film version of Psycho, which became his most commercially successful film and entirely changed the horror-movie genre.

There have been horror movies as long as there have been movies. But whereas former classics such as Dracula and Frankenstein were based on semi-human monsters and were constrained by the prudish mores of the era, Psycho was produced shortly after the Motion Picture Production Code that had been in place since 1930 had begun falling apart. In this case, the monster was an ordinary (if extremely tortured) human being, and his violence was explicitly shown rather than merely hinted at.

For some reason, it’s much harder to deal with monsters when they’re human.

Even the opening scene featuring unwed lovers Marion Crane and Sam Loomis sitting together in bed, with Marion wearing a bra, would have been prohibited if the film had been made only a few years prior.

The deep psychosexual subtexts involving gender dysphoria and a confused man with murderous mommy issues would never have slipped past the censors. Psycho also bears the dubious honor of being the first major Hollywood film to show a toilet flushing.

Psycho is widely considered the first “slasher” movie, although a little-known British film called Peeping Tom featured similar themes and was released a few months prior to Psycho. But due to its themes of sex and violence compounded by its runaway success, it changed the horror game forever and can rightfully claim the title of the most influential horror movie ever made.

Every horror film that came in its wake owes at least a partial debt to Psycho. A stellar example of this is that in the first film in the Halloween series, Jamie Lee Curtis is terrorized by a psychopath much the same way her mother, Janet Leigh, was in Hitchcock’s classic.

According to the “Critics Consensus” at Rotten Tomatoes, “Because Psycho was filmed with tact, grace, and art, Hitchcock didn’t just create modern horror, he validated it.”

As the cinematography abruptly switches from deep darkness to harsh light again and again, the viewer realizes that the film is about guilt and redemption. Both major characters—Norman Bates and Marion Crane—are tortured by their past and their own misdeeds to the point where their own guilt swallows them whole. Even though the main culprit is caught, there is no happy ending in this film. This suggests that there is no easy way—or maybe no way at all—to escape one’s past.

Trailer

There were two official trailers issued for Psycho—a six-minute version narrated by Hitchcock, and a more traditional two-minute version that shows vital scenes.

Although Psycho was far more explicit in its violence than any horror movie that preceded it, the horror genre often relies more on what’s implied than what’s shown, a technique Hitchcock employs brilliantly in his six-minute trailer:

Here a morose and nearly emotionless Hitchcock leads the viewer around the Bates Motel premises and up into the creepy house on the hill. He only hints at all the terror emanating from this isolated compound but always backs off before describing exactly what it is—until the final sequence, where he walks into Cabin #1 and pulls back a shower curtain.

The two-minute trailer takes almost the complete opposite approach and begins with the shower scene, punctuated by the stabbing violin strings that comprise perhaps the most famous horror-movie music in history. It’s a densely packed one minute and forty-one seconds that compresses the two-hour film’s suffocating tension to the point where viewers may find themselves gasping for air.

Plot

The film begins in the relentless sunshine of Phoenix, Arizona, then the camera suddenly zooms into the thick darkness of a motel room somewhere in downtown Phoenix, where Marion Crane and her debt-addled, long-distance boyfriend Sam Loomis have just completed a lunchtime sex romp. The first we see of Marion, she’s in bed and wearing a bra, which was absolutely scandalous in 1960.

After the couple discusses the fact that Sam’s debts amount to an obstacle that prevents them from getting married, she returns to her job, where a drunken and flirtatious cowboy client plops down $40,000 in cash (equivalent to about $350K in 2020) as a down payment on a house. Marion’s boss instructs her to take the cash and deposit it in their local bank.

Instead, Marion packs her suitcase, keeps the $40,000, and starts driving toward Sam’s residence in Northern California. Road-weary and blinded by oncoming headlights, she parks roadside and falls asleep the first night.

She is awakened the next morning by a highway patrolman in dark sunglasses whose suspicions are aroused simply by the fact that Marion is acting so suspiciously. He tails her to Bakersfield, where she swaps out her car for a used car. She continues driving the new car into the night, at which point pounding rain has her pulling off into a creepy little out-of-the-way place called the Bates Motel—probably the most famous motel in film history.

The proprietor is a shy, skinny guy named Norman Bates, who lives on a craggly, creepy, haunted-looking house on the hill overlooking the motel. He tells Marion that the hotel has been in decline ever since a new highway diverted all traffic away from it. He makes Marion a sandwich and reveals to her that he’s been caring for his elderly and ill mother in the house on the hill. After their quiet and painfully polite little dinner, Marion tells Norman that she’s tired and is going to shower before she falls asleep.

Marion is in Cabin #1, which is directly adjacent to the motel office, and as Norman returns to the office, we see the first suggestion that he has a screw loose somewhere inside his head—he removes a painting on the wall and peeps through a hole at Marion undressing in her room.

Next comes what has often been described as the most famous scene in movie history—as Marion is showering, we suddenly see a dark figure enter the bathroom, but it’s obscured by her shower curtain. As composer Bernard Herrmann’s famous unhinged violins signal danger, the silhouetted figure pulls back the shower curtain to reveal an elderly woman wielding a giant knife, which she uses to stab Marion to death.

Then we see Norman come running out of the house on the hill looking for his mother, only to discover to his alarm that she’s murdered Marion. A true mama’s boy, he meticulously cleans up the crime scene and disposes of Marion’s body—as well as the $40,000 in cash, which he didn’t realize was folded in a newspaper—in the trunk of her car, which he rolls into a swamp near the motel premises.

This is around when Marion’s boss realizes she never deposited his client’s $40,000 in the bank. It’s also when Marion’s sister Lila realizes she’s missing and drives all the way to Northern California to confront Sam about it.

While she’s confronting Sam, in walks Private Investigator Milton Arbogast, who’s been hired by Marion’s boss to find her and hopefully retrieve the money without anyone getting arrested. Neither Sam nor Lila has any idea where Marion is, so Arbogast begins visiting local motels until he finally arrives at the Bates Motel.

Norman is at first friendly but grows increasingly nervous and hostile as Arbogast questions him. After initially denying that anyone has stayed at their dilapidated motel in weeks, his books reveal that a woman did indeed stay at the motel under a pseudonym, and her handwriting matches Marion’s. Norman makes the mistake of saying that although he never spoke with Marion, his mother did, leading Arbogast to request an interview with Mrs. Norman Bates in that ghastly old house on the hill. Norman says that’s probably not a good idea and that Arbogast should leave both him and his mother alone.

Arbogast is a stubborn detective, though, and when he enters the house calling for Mrs. Bates, she meets him at the top of the stairs and stabs him to death.

Lila and Sam grow suspicious when they don’t hear back from Arbogast, so Sam heads out to the motel to grill Norman. When the interrogation yields nothing, Sam and Lila head out in the middle of the night to wake up the local sheriff, who comes down in his robe to inform the pair—to their understandable alarm—that Mrs. Bates died ten years ago after poisoning her lover and then herself with strychnine.

As Sam and Lila drive back to the motel to demand answers, we hear Norman and his mother loudly arguing, then see an overhead shot of Norman carrying his mother down to the house’s fruit cellar against her objections.

While Sam distracts and flusters Norman by asking him a series of increasingly penetrating questions, Lila enters the house in search of Mrs. Bates. She’s not in her bedroom, nor is she in Norman’s room, although Lila pauses to note how strange it is that his room is filled with stuffed animals and childhood toys.

When Sam’s questions become too much for Norman to bear, Norman smashes him over the head with a blunt object, knocking him unconscious. Norman then runs toward the house on the hill.

Having found nothing on the house’s upper floor, Lila finally creeps down to the fruit cellar, where it appears that Mrs. Bates is sitting in a rocking chair with her back to Lila. But when she grabs Mrs. Bates’s shoulder, what spins around is a dried-out corpse.

Lila screams, and we see Norman—dressed in a wig and a woman’s dress and wielding a giant knife—lunging toward Lila to kill her. But he is stopped at the last moment by Sam, who has regained consciousness and wrestles the knife away from him.

The next scene shows the courthouse where Norman has been taken and examined by a psychiatrist.

The psychiatrist explains to Lila and Sam that Norman started spiraling into mental illness after his father died. It became worse when his mother took a lover, which drove Norman insane with jealousy. Norman killed both his mother and her lover, but the guilt was so overwhelming that he stole her corpse and began acting as if was still “alive.” To keep her “alive” in his mind, he adopted an alternate personality that wore his mother’s clothes and talked in her voice. The new “mother” personality was as jealous as Norman was. Whenever Norman found himself enraptured with a new girl, the “mother” had to kill the girl.

It turns out that not only did Norman kill his mother and her lover, as well as Marion Crane and Detective Arbogast—in between those murders, he’d killed two separate girls for whom he’d developed a sexual attraction.

The psychiatrist notes that Norman’s mother had been so domineering, she was always a part of his personality. But as time went on and Norman’s guilt festered, his mother completely took over his personality: “He was never all Norman, but he was often only Mother.”

In a closing scene that is almost suffocatingly creepy, we see Norman sitting alone in a holding cell as his mother’s voice narrates. She explains that Norman had been the killer all along. Then, paradoxically, she notes that there’s a fly crawling on his hand and he doesn’t even swat at it, because her boy “wouldn’t hurt a fly.”

In the closing scene, we see Marion’s car being pulled from the swamp.

Differences Between the Novel and the Film

Hitchcock originally hired Alfred Hitchcock Presents screenwriter James P. Kavanaugh to pen the screen adaptation, but Hitchcock was dissatisfied with the results and reportedly said it came off like a plodding TV script. He then hired a relative unknown named James Stefano to write the screenplay instead. At the time he wrote the script, Stefano was in therapy dealing with his own maternal issues.

Among Stefano’s alterations:

- Instead of the middle-aged, overweight lunatic depicted in the book, Stefano reworked Norman Bates as a fit, young, friendly man—if a little “off.”

- Whereas Norman’s excessive drinking usually led to his episodes where he “became” his mother, this element was eliminated from the film.

- In the book but not the movie, Bates was interested in porn and the occult.

- Whereas Marion Crane is mentioned in only two of the book’s 17 chapters, she is the film’s central feature for the first forty-five minutes. The novel starts with Norman Bates reading a book, but his character doesn’t even appear until 20 minutes into the film.

- The opening love scene between Sam and Marion was Stefano’s creation entirely. It was not in the book.

- Whereas Sam winds up explaining the roots of Norman Bates’s psychosis to Lila in the novel, in the film a psychiatrist does the big reveal about how Norman “became” his mother. Most notably, when another cop says that Norman was a “transvestite,” the psychiatrist says “not exactly” and goes on to explain how psychologically, Norman actually became his mother, an extremely radical concept in 1960.

Cast

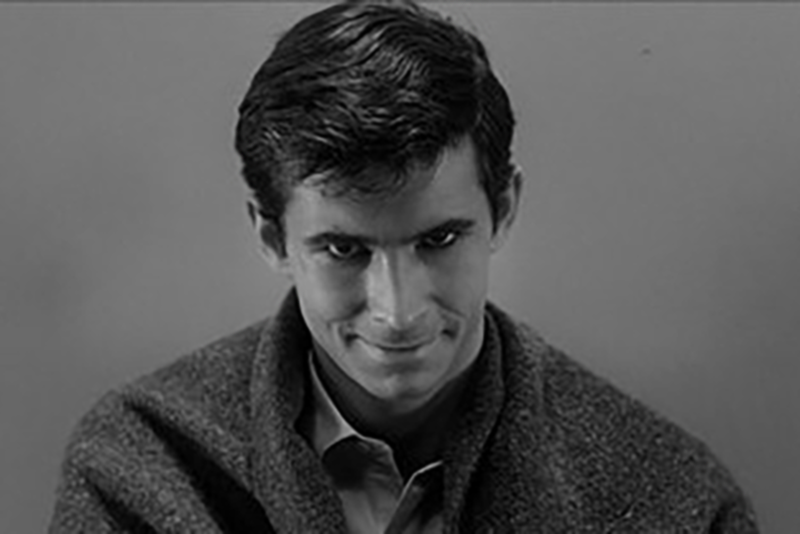

(Wikimedia Commons)

Anthony Perkins is Norman Bates, the lonely, crossdressing, mentally ill proprietor of the Bates Motel whose shy, friendly, aw-shucks demeanor belies the fact that he’s a serial killer.

Janet Leigh is Marion Crane, an attractive but bored Phoenix secretary who steals $40,000 so she can build a life with her lover—and then regrets stealing it after it’s too late.

Vera Miles is Lila Crane, Marion’s sister who tracks down Sam Loomis in an attempt to find her missing sibling.

John Gavin is Sam Loomis, Marion’s debt-ridden boyfriend who heads out to the Bates Motel to investigate after Marion goes missing.

Martin Balsam is Private Investigator Milton Arbogast, who asks hard questions but winds up as one of the two people we see getting murdered in the film.

John McIntire is Deputy Sheriff Al Chambers, who startles Sam and Lila when he reveals that Norman Bates’s mother has been dead for ten years.

Simon Oakland is Dr. Richmond, the psychiatrist who interviews Norman after his arrest and concludes that Norman’s mother has taken over the killer’s mind.

The Shower Scene

This scene is often described as the most famous in all of cinematic history.

One of the most disconcerting things about Psycho, and a major reason it marks a major departure from previous horror films, is that the main character gets killed less than halfway through the movie. Until that point, the audience has good reason to believe that Marion Crane is the “psycho” in the title.

According to Hitchcock:

As you know, you could not take the camera and just show a nude woman, it had to be done impressionistically. So, it was done with little pieces of film, the head, the feet, the hand, etc. In that scene [just the stabbing] there were 78 pieces of film in about 45 seconds.

The sound of the knife slashing into flesh was reputedly the sound of a knife slashing into a casaba melon. The “blood” that we see splattering all over the tub and swirling down the drain was reported to be chocolate syrup. One of the reasons Hitchcock said he decided to film in black and white rather than color — besides saving money — was because he was certain the censors would not allow full-color gore. That would come three years later with what is widely considered the first “splatter” film, Blood Feast.

Both Janet Leigh and Alfred Hitchcock say the shower symbolized Marion Crane’s purification, her repentance and decision to return to Phoenix and give the money back. But sometimes a crazy old woman with a giant knife comes along to disrupt the best-laid plans of bored, lovelorn secretaries.

Despite the scene’s short length, it took about a week to film. Janet Leigh had to get around both a seasonal cold and her period in order to film it. She was so traumatized by the experience — especially the fact that she never realized “how vulnerable and defenseless one is” while showering — that she purposely avoided showers for the rest of her life.

Psycho’s Music/Soundtrack

Regular Hitchcock composer Bernard Herrmann initially refused to accept a reduced fee for scoring the new film but agreed when he realized he could convey sheer terror with only stringed instruments instead of a full orchestra. Hitchcock initially said he didn’t want any music for the film’s centerpiece, the shower scene. But after a test viewing revealed that moviegoers weren’t quite horrified by the shower scene, he included Herrmann’s music, which might be the most iconic usage of music in film history. Although some speculated that Herrmann also included musique concreteelements such as screeching birds on the track called “The Murder,” it was all done with stringed instruments held painfully close to the microphone. Hitchcock later stated that “33% of the effect of Psycho was due to the music,” which may be an understatement. Only the looming music in Jaws that signals the shark’s arrival comes close to Psycho’s famed ability to convey horror through music.

Psycho’s Budget

Since Paramount Pictures didn’t want any part of Psycho, Hitchcock decided to work around them.He purchased rights to the 1959 novel by Robert Bloch—who lived near to Wisconsin killer Ed Gein and was partially influenced by his story—for $9,500 and waived his typical director’s fee of a quarter-million dollars in exchange for a 60% stake in the film negative, a decision which wound up netting him an estimated $15 million.

Both Janet Leigh and Tony Perkins were already established film stars by this time, but they also accepted a drastically reduced fee simply to be in a Hitchcock film. Black-and-white film as well as a pared-down musical budget — as well as using his own TV crew from Alfred Hitchcock Presents to film it — enabled him to complete production for $807,000. The film wound up grossing approximately $50 million, making it the most successful movie in Hitchcock’s storied career.

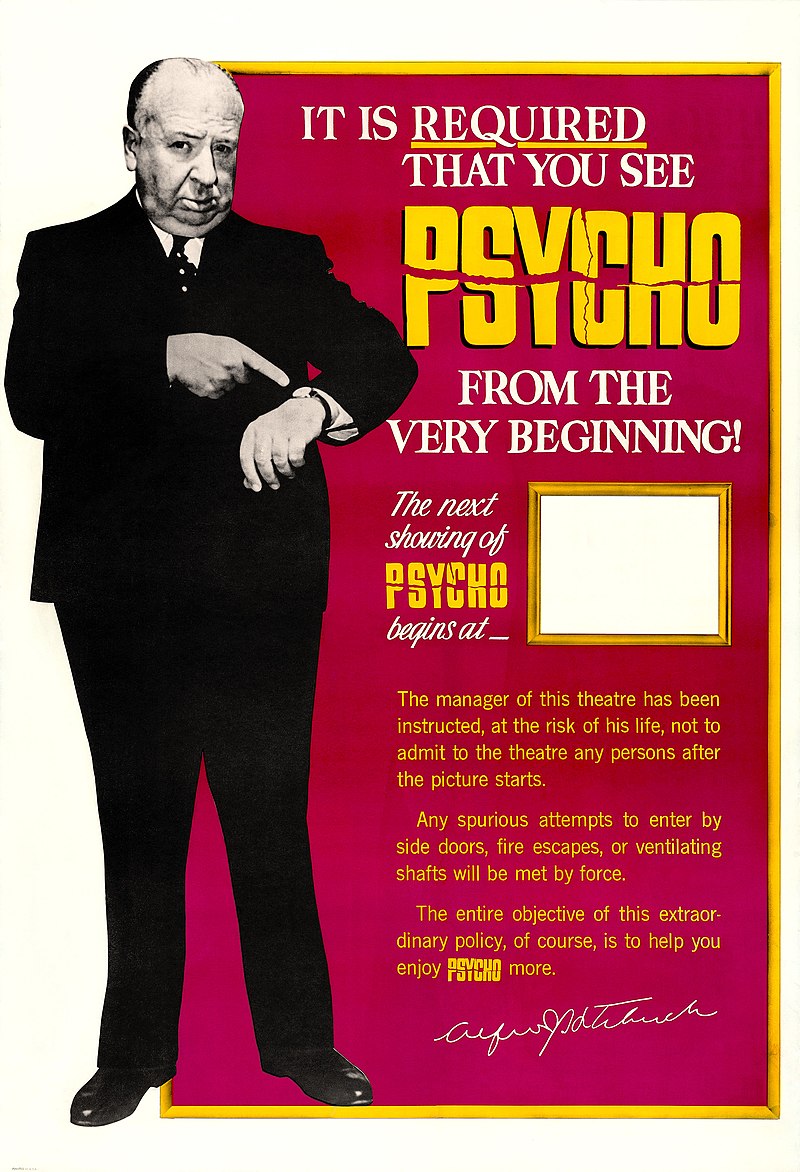

Unique Promotion/Marketing

Hitchcock did nearly all of the promotion himself. He forbade his actors from doing interviews about the movie because he didn’t want anyone to spoil the ending. He also made them sign non-disclosure forms agreeing not to discuss the movie. With a motto of “Don’t give away the ending—it’s the only one we have!,” he even had an assistant try to buy up all remaining copies of Psycho the novel for the same reason.

Hitchcock lured in moviegoers by proclaiming:

It has been rumored that ‘Psycho’ is so terrifying that it will scare some people speechless. Some of my men hopefully sent their wives to a screening. The women emerged badly shaken, but still vigorously vocal.”

Critics were not given private screenings and were forced to attend the film along with the general public—who, due to an ingenious marketing strategy were not allowed into the theater after the film started. Hitchcock borrowed this concept from French director Henri-Georges Clouzot, who had instituted a “no late admissions” policy for his 1955 film Les Diaboliques. Part of the reason he did this was so that late-arriving moviegoers wouldn’t feel cheated after realizing that the film’s star had already been killed.

Possibly miffed at not receiving their usual special treatment, many critics dismissed Psycho upon first glance, sneering at is as a “low-budget job,”

“a blot on an honorable career,” and “plainly a gimmick movie.” But in the wake of the film’s roaring success, many critics reevaluated their stances, and Psycho is now widely considered one of the greatest films ever made.

Psycho: Fun Facts

- Hitchcock typically made a cameo in all of his films. In Psycho, he appears at about the six-minute mark, wearing a cowboy hat outside Marion Crane’s office:

- The “Bates Motel” and the house on the hill were on the set of Universal Studios—and still are to this day, making it one of the most popular attractions in the entire studio tour.

- Hitchcock received an angry letter from a father claiming that after watching Psycho, his daughter refused to take showers. Hitchcock reportedly replied, “Send her to the dry cleaners.”

- Censors initially blocked the film’s release because some of the reviewers said they could spot a breast in the shower scene. Without editing a frame, Hitchcock resubmitted the scene, and the same editors who first saw the breast didn’t see it this time, while those who didn’t see it now saw it. Hitchcock was able to release the scene untouched.

- The film received four Academy Award nominations—including Best Director for Hitchcock and Best Supporting Actress for Janet Leigh—but failed to win any prizes.

- Movie mogul Walt Disney banned Alfred Hitchcock from filming at Disneyland after the film came out because he made “that disgusting film, Psycho.”

- Norman’s chilling statement that “A boy’s best friend is his mother” is considered one of the best lines in film history.

- During the filming, Hitchcock always referred to Anthony Perkins as “Master Bates.”

- Although Psycho was the first film to be inspired by the story of real-life Wisconsin killer Ed Gein, he later became the inspiration for The Texas Chain Saw Massacre(1974) and Silence of the Lambs(1991).

- Because Marion stole a lot of money to be with Sam, his last name of “Loomis” is a reference to the Loomis armored-truck company.

- To rattle Janet Leigh, Hitchcock kept surprising her by placing the “corpse” of Norma Bates in unexpected places on the set during the filming.

- In the first scene, Marion wears a white bra, signifying innocence. After she steals the money, she is shown wearing a black bra.

- Anthony Perkins was paid $40,000 for his role—the exact amount Marion Crane embezzled in the film.

Sequels

Hitchcock never made a sequel to Psycho, but then again, he operated during a time when Hollywood tried to stick with original material and rarely made sequels to any films.

After his death in 1980, though, four sequels were made: Psycho II (1983), Psycho III (1986), Bates Motel (1987), and Psycho IV: The Beginning. (1990). Except for Bates Motel, all the other sequels starred Anthony Perkins as Norman Bates. Perkins also directed Psycho III.

In 1998, filmmaker Gus Van Sant produced a controversial remake of Psycho that imitated the original version shot-by-shot. It starred Vince Vaughn as Norman Bates and Anne Heche as Marion Crane and was both a commercial and critical flop, but that’s what you get for trying to fix what ain’t broke.

In 2013 A&E launched a dramatic series called Bates Motel that was reset in the modern day and focused on Norman’s childhood and what turned him into a killer. It lasted for 50 episodes.

Best Way to Watch/Stream

Psycho is currently not available for streaming on Netflix—the American version of Netflix, that is. It is streaming currently on Hulu, Starz, Starz Play Amazon Channel, and DIRECTV. It is available in Blu-ray, 4K, and DVD formats. Psycho can be rented for $3.99 or bought for $7.99 on Amazon Prime; it can also be rented for $3.99 at VUDU, iTunes, and Google Play.