13 Queer-Coded Monsters In Horror Movie History

Because horror and queerness have always gone hand in hand and the monster has always amplified the “otherness” of the LGBTQ+ community.

Horror has gone hand in hand with queerness since its origins. Mary Shelley, the mother of modern horror and known to be bisexual, wrote Frankenstein in 1818 infused with queer undertones. Other early works with gay subtext include Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), and J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s literary classic Carmilla (1872). Monsters in the Closet author Harry M. Benshoff writes:

Both movie monsters and homosexuals have existed chiefly in shadowy closets, and when they do emerge from these proscribed places into the sunlit world, they cause panic and fear. Their closets uphold and reinforce culturally constructed binaries of gender and sexuality that structure Western thought. To create a broad analogy, monster is to ‘normality’ as homosexual is to heterosexual.

Since the beginning of horror on screen, it has been largely creatively governed by queer talent. During the era of the Hays Production Code and before it was “acceptable” to come out, filmmakers discovered in creature features the leeway required to share LGBTQ+ stories thinly veiled as horror—stories in which other members of the queer community could see themselves in, that they could relate to, and with aspects that could resonate only to them. English film director James Whale, openly gay throughout his career, brought much success to movie studios in the 1930s, and is known for Frankenstein (1932), The Old Dark House (1932) The Invisible Man (1933), and Bride of Frankenstein (1935)—all films notorious for queer subtext.

Despite the Hays Code being lifted in 1968, queer representation continues to hide in the dark and shadows alongside the monsters. The monster and the LGBTQ+ person can understand each other because both have an “otherness” about them. Both are misunderstood by the heteronormative status quo and both are often feared or hated for no other reason than being different. Horror amplifies our “otherness” and serves as a rich tapestry for LGBTQ+ expression.

The below list is by no means an exhaustive one, as examples of gay subtext are endless in the genre, but it does include some of the most iconic queer-coded monsters in horror movie history. Check them out below.

Count Orlok in Nosferatu (1922)

One of the earliest and most iconic horror films was directed by gay filmmaker F.W. Murnau. This silent German Expressionist adaptation of Bram Stoker’s famous novel Dracula (1897) is infused with gay subtext. Transylvanian vampire Count Orlok (Max Schreck) is representative of a man made monstrous by his homoerotic desires, much like society paints queer people out to be. Count Orlok bites the necks of men and tries to invade their dreams. His pupils dilate when he stares at Thomas Hutter (Gustav von Wangenheim). He watches him undress in a highly suggestive scene, and his eyes become wider and wider. The vampire can’t help himself because it’s in his nature, as being gay was in Murnau’s. More than that, however, Count Orlok is emblematic of Hutter’s repression of his own sexuality by acting as a reflection of the latter’s “shadow self.” His queer desires are evident earlier in the film before he embarks to Transylvania when he leaves his wife Ellen (later renamed Nina and played by Greta Schröder) with a sexless and passionless kiss. Him forgetting being bitten by Orlok signifies him repressing the sexual experience because of his own internal homophobia.

The Monster in Frankenstein (1931)

The film is essentially a story about a homosexually repressed man creating his dream male companion. Instead of taking the heteronormative route and creating life with a woman, Dr. Henry Frankenstein (Colin Clive) takes it upon himself to make life through the assembly of male limbs. The Monster (Boris Karloff) serves as the embodiment of Henry’s queer desires and attraction to men. The doctor is far more interested in his pursuit of fabricating life than he is in a marriage to Elizabeth (Mae Clarke), on which his father insists. Near the beginning, Elizabeth discusses Henry’s bizarre actions and experiments with their friend Victor (John Boles), hinting at the “otherness” of the scientist. When Henry succeeds at creating life, he’s afraid of what he’s created. He doesn’t want to be around the monster, alienates, and abandons him—an experience LGBTQ+ people are all too intimate with. The monster is seen as “other” simply because he looks and acts differently. They can’t understand that he was simply born that way. This emphasizes that queerness isn’t a choice. The Monster is rejected for simply existing and driven out of town with pitchforks—an eerie parallel to society’s treatment of queer people.

The Bride in Bride of Frankenstein (1934)

There’s more to Bride of Frankenstein than the obvious gay subtext between Dr. Frankenstein and Dr. Pretorius (Ernest Thesiger). The film is a rejection of heteronormativity. The Bride (Elsa Lanchester) is symbolic of the extreme societal pressures for heterosexual marriage and starting a family. After the two scientists animate her, she is walked out by Dr. Pretorius to meet The Monster, like a father with a bride down an aisle. Upon meeting her mate, she displays disgust and revulsion, immediately rejecting him. She was made simply to be the wife of The Monster and to please the scientists, but she will not accept such fate. This is a reflection of the expectations queer people suffered and continue to suffer from. Even in the end, it’s only the two people who will submit to the heteronormative status quo that survive.

The Countess in Dracula’s Daughter (1936)

There’s abundant lesbian subtext in Dracula’s Daughter, one of the earliest examples of the gay predatory trope in film. The narrative centers around Countess Marya Zaleska (Gloria Holden) who longs to be normal and set free from her unnatural desire to feed on other women. At the beginning of the film, she burns her father’s body in the hopes that it will cure her of vampirism, which is a metaphor for her sapphic urges. Afterwards, she confides in her servant her hopes that her curse will be lifted and that she’ll finally be able to “live a normal life now, think normal things.” When she’s accused of “concealing the truth” about herself by Dr. Garth (Otto Kreuger), she responds that the truth is “too ghastly.” Her inner conflict is her lesbianism. In one of the film’s final scenes, she’s more interested in kissing Janet (Marguerite Churchill) than she is in killing her. The lesbian subtext is there and was meant to be there.

The Wolf Man (1941)

This film is a symbol for America’s fear of querness at the time, with the werewolf being a metaphor for homosexuality. Larry (Lon Chaney Jr.) is forced to live a double life after he is attacked and bitten by a werewolf. He is now cursed, just as many in society viewed queerness as curse, but it’s also something that is out of his control. A gypsy woman informs him that the only way to cure himself is by death. This emphasizes the ignorance and malice of society in attempting to cure something that isn’t curable. In the end, Larry meets a brutal demise for not conforming to normativity.

Irena in Cat People (1942)

Irena (Simone Simon), a young and lonely Serbian fashion illustrator living in New York City believes she has an ancient familial curse affecting the women in her lineage that will turn her into a lethal panther if she becomes aroused. She makes this confession to her new husband Oliver (Kent Smith) on the night of their honeymoon. Although they try, they fail to consummate their marriage. Irena genuinely tries to be interested when the man tries to get physical with her, but something inside her doesn’t allow her to be the perfect (straight) wife she longs to be. Her character is representative of the shame and fear attached to the realization that you’re not “normal,” as well as of the desire to fit into society’s standards and expectations. Oliver becomes frustrated and grows closer and closer to his coworker Alice (Jane Randolph), whom Irena tenses up around. Her sexual repression is evident through the screen. Irena becomes obsessed with Alice not because of jealousy, but passion and desire. She transforms into a panther as she stalks her, unable to control her lesbian urges. The movie has plenty of subtle scenes where other characters comment on Irena’s strange look and the “otherness” about her, further contributing to the lesbian coding.

Bill in I Married a Monster From Outer Space (1957)

The film follows Marge (Gloria Talbot) who has become increasingly concerned about her husband Bill (Tom Tryon) who doesn’t seem to display any genuine affection for her. A year into their marriage he has grown and emotionally detached. It isn’t long before she takes notice that the rest of the husbands in the neighborhood are displaying similar behavior. Soon she discovers that her husband isn’t actually her husband, but an alien from a planet where all the women have gone extinct and who has taken on Bill’s form. It’s a classic closeted gay man with a beard wife story with abundant queer undertones and themes, such as cruising.

Norman Bates in Psycho (1960)

Alfred Hitchcock is notorious for working with gay actors and for queer coding characters in his movies. Such examples can be seen in The Lady Vanishes, Rebecca, Rope, and North by Northwest. Psycho is undeniably queer-coded, as well. Norman’s toxic obsession with his mother served as a hint to his sexuality during an era in which this trait in a man translated into being gay. The character might not have been explicitly gay, but plenty of aspects hinted at his sexuality. Hitchcock handpicked Anthony Perkins, a known but closeted gay man, to play the role of the soft-spoken, crossdressing killer. Before Marion (Janet Leigh) turns into his victim he says to her in a scene, “I think that we’re all in our private traps, clamped in them, and none of us can ever get out. We scratch and we claw but only at the air, only at each other, and for all of it, we never budge an inch.” Lila (Vera Miles) tries bribing him with money and telling him he can start over in a new place where he might be accepted for who he is. The film isn’t without problematic aspects, as Norman’s villainous nature is inflamed by his “otherness” in the big reveal.

David and the Vampires in The Lost Boys (1985)

The Lost Boys is an extremely queer-coded movie—and not just because Tim Capello makes a cameo bathed in baby oil while writhing onstage. From the narrative to the fashion choices to the soundtrack to the subtext, the film just screams gay. David (Kiefer Sutherland) essentially courts Michael (Jason Patric) into “becoming one of them.” When Michael is drinking what he doesn’t believe to be blood but actually is, David looks at him with hunger and desire in his eyes. There’s definitely a sexual energy and chemistry between the two. Hanging from the train tracks, he encourages Michael to let go and says, “You’re one of us now.” The metaphor speaks for itself. This notion is further supported by the homophobic undertones seen in the movie, such as when Edgar Frog (Corey Feldman) declares, “We’re fighters for truth, justice, and the American way” and hands Sam (Corey Haim) a comic book titled “Destroy All Vampires.” When Sam realizes what has happened to his brother after falling in with the wrong crowd, Sam screams at Michael, “’My own brother, a goddamn, shit-sucking vampire!” It’s worth noting that the director Joel Schumacher is openly gay.

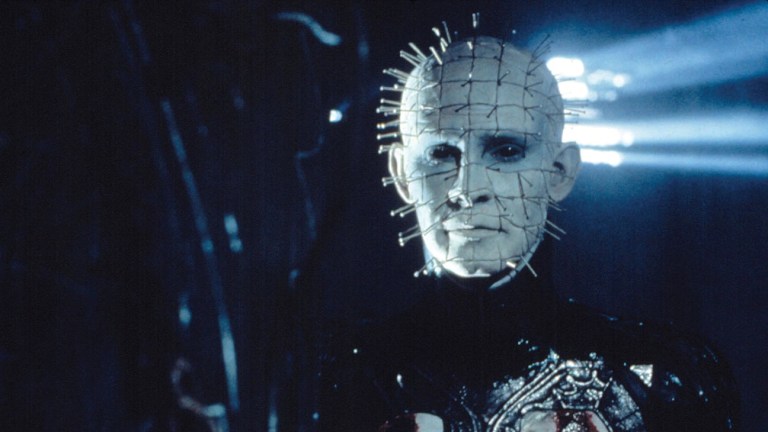

Pinhead in Hellraiser (1987)

Pinhead was adapted from the director’s 1986 novella, The Hellbound Heart. Clive Barker, openly gay and proud himself, has said that the iconic leather-clad Hell Priest and Lead Cenobite was inspired by his experiences at an underground S&M club. The whole film itself reads as a homage to queerness and otherness, not to mention a celebration of BDSM. Pinhead (Doug Bradley) has not only cemented himself as a horror icon, but also as an icon to the LGBTQ+ community.

Lestat in Interview With a Vampire (1994)

A male vampire choosing another man to turn to make him a lifelong companion? Then they raise a child together? The movie is much more subtle than the revamped and unapologetically queer AMC+ series, but just as in the book, the writing is on the wall. Not only does the film have abundant homoerotic bloodsucking scenes, moments of unbridled passion and gay subtext in the dialogue, but Anne Rice herself confirms that Louis and Lestat are a same sex couple.

Billy Loomis and Stu Macher in Scream (1996)

For all intents and purposes, Billy (Skeet Ulrich) and Stu (Matthew Lillard) were monsters. This list wouldn’t be complete without this heavily queer-coded psychotic duo. There’s more besides the obvious required intimacy and profound connection it would take to plan a murder together. They’re portrayed as having a homoerotic closeness. When Billy has Sidney (Neve Campbell) cornered in the kitchen and is pointing a knife at her chest, Stu embraces Billy from behind and rests his face on his shoulder. There is also a brief—but very obvious and intense—moment where Stu eyes Billy’s neck with longing. The whole kitchen scene is filled with sexual tension between them, especially on Stu’s part. He keeps referring to Billy as “baby” and “babe” as he psyches himself up for getting stabbed by his partner in crime. Manipulative Billy likely saw Stu’s infatuation with him and exploited it to carry out his plan.

Babadook (2014)

Mister Babadook was jokingly memefied on Tumblr as gay, people ran rampant with it, it spilled over into mainstream media, and eventually the monster was cemented as a contemporary gay icon. However, it wasn’t just a meme and a top hat that turned Babadook into a Pride Month figurehead. Although the film wasn’t intended to be queer, through an LGBTQ+ lens it can be viewed as a metaphor for the desire to come out but feeling unwanted and unseen. The entity of Mister Babadook himself can be seen as queer. His confinement in the basement mirrors the pain many queer people have faced when their own families have refused to acknowledge their sexuality. “The more you deny, the stronger I get” are words that resonate with those who have experienced the struggle of denying their own identity.

Further reading: