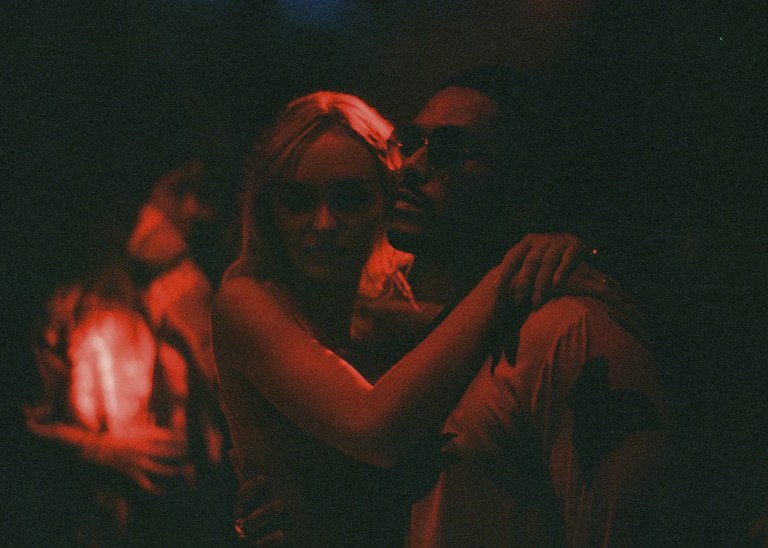

Is Sam Levinson’s ‘The Idol’ Actually A Horror Movie?

Sam Levinson’s The Idol is a radical departure from Euphoria. Euphoria deals with common problems. Opiate addiction, sadly, is a universal theme. The psychedelic insanity of youth, naturally, is a universal theme.

Turning the subject matter to Hollywood’s seedy underbelly, which is also its top echelon, is an exotic subject that, however real, is deeply unrelatable. Although we know this culture destroys people brought up in it, and I woudn’t wish fame on even my worst enemy’s children, we still have a hard time processing just how malicious the spotlight is on young people. Because how can being rich, famous, and beautiful be so painful?

As I scanned the first episode of The Idol, it was hard to classify the genre. The first thing that came to mind in terms of style was The Informers (2008), a movie based on a Bret Easton Ellis book of the same name, merged with Vox Lux (2018), with elements that seemed to be spoofing while taking seriously 90s erotic thrillers like Basic Instinct (1992).

There was also an element of the horror genre that seemed to be peeking through. The cinematography felt reminiscent of Ari Aster’s Hereditary (2018) and other a24 films. The over-sexualization, or explicit pornographic element with a specter of the hammer about to drop at any given moment, also felt uniquely in the tradition of horror cinema.

So, what genre exactly is The Idol? Is it horror?

One theoretical way to think about horror is as story configurations with a subversive narrative structure — and given the mainstreaming of horror movies in general, it’s almost impossible for even gruesome movies like the Saw franchise or intense ones like Smile (2022) to be subversive because they are already so mainstream. The devils of mainstream horror aren’t devilish anymore; they’ve been assimilated. Enter Tedros.

So, considering the violent reaction to The Idol, it certainly qualifies as a subversive narrative that is wreaking havoc at the corporate headquarters of HBO and redefining the careers of the stars; maybe not in a good way.

The thought, “how in the world did one of the greatest pop stars of the 2010s end up playing a psychotic cult leader in an art house horror film bordering on a BDSM porno? And how did we get to the place where there could be such a large budget behind a show like this?” is evidence that The Idol is actually a rare media virus that somehow made it through the Hollywood bureaucracy and hatched something subversive.

Okay, though, to what end? It seems the common consensus is that while shocking, there is no point to the shock value except for a rushed storyline that is nauseating just for the sake of being nauseating, not doing anything that interesting in terms of artistry and philosophy. I suppose you could say that about the Saw franchise as well though, and a number of gruesome horror films.

It’s utterly clear to me that the most interesting and thought-provoking point about The Idol is that Tedros is actually making Jocelyn a better artist. But at the same time, you’re utterly disgusted by him and fear for Jocelyn’s life. Fearing for Jocelyn’s life does not seem like an overreaction, as it does feel like at any second the plot might twist and turn itself into a kidnapping or murder narrative. Still, while you fear for her, you also can’t help but question whether Jocelyn is more in control than she seems — could she be the true puppet master behind the events unfolding? Is she even more genuinely unhinged than Tedros?

And I’m certainly watching The Idol in the context of a Faustian tale, in many ways reminiscent of Rosemary’s Baby (1968) —where a man offers his firstborn to a Satanic cult in exchange for success in Hollywood; again another bullet point deeply aligning The Idol within the horror genre.

So, yes, the art is better; gone is that bubble gum crap, and deep, provocative music takes over; but at what cost?

When discussed above, the theme of the show does not seem that controversial, but the question, “Is all art the work of the devil?” which has been a concern for human culture since at least the times of Socrates, who posited that we had to banish poets/musicians from society to have a healthy culture, is a hornet’s nest of a topic that unlocks all sorts of cultural wars.

I would say then that Tedros — or maybe Jocelyn — are best understood in literary terms as Satan-like characters and the act of creative collaboration is rendered in the show as a mode of demonic possession. It’s worth noting the ancient Greek term δαίμων (daimōn) where we get the word demon from originally referred to a guiding spirit of genius, and Levinson’s teleplay seems to to play with this in explicit ways. What does it mean to surrender to the daimōn, or the demon?

If Tedros is a genius, and Jocelyn, irrespective of whether she is using him or being used by him, is creating genius art in collaboration with him; what are the implications? The answer is something undoubtedly horrible and blasphemous to secular society. Healing? Trigger warnings? Equality? Safe spaces? Tedros is the anathema of it all. The idols are demonic.