‘Let’s Scare Jessica to Death’ (1971): A Dreamy (and Terrifying) 70s Horror Film

Despite being relatively unknown, the film has the distinction of being called “one of the scariest films ever made” by the Chicago Film Critics Association and is a favorite of Stephen King.

Let’s Scare Jessica to Death (1971) is a gem of 70s independent horror, though it has largely been overshadowed by other indie horrors from the decade such as The Last House on the Left (1972), The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), Dawn of the Dead (1978), and Halloween (1978). Despite being relatively unknown, the film has the distinction of being called “one of the scariest films ever made” by the Chicago Film Critics Association and is a favorite of Stephen King and the Twilight Zone‘s Rod Serling, who called it one of the most frightening films he’d ever seen.

Table of Contents

Throats are certainly getting ripped out, but that’s not the specific fear Jessica is feeling for most of the film’s runtime. It’s the terrifying suspicion that she’s either losing her mind again, or, worse, that she’s not and nobody around her will believe her.

Kenneth Lowe, Let’s Scare Jessica to Death Is 50, but Its Portrayal of Gaslighting Is Timeless

‘Let’s Scare Jessica to Death’ Synopsis

The film follows the title character, Jessica (Zohra Lampert), who has just left a psychiatric care facility. Her husband, Duncan (Barton Heyman), has quit his job so that the couple can move (along with their hippie friend Woody, played by Kevin O’Connor) from New York City to a newly purchased rural farmhouse where Jessica will continue her recovery. Unfamiliar with the area, the trio is at first surprised to discover hostility from the locals, who Jessica notes all sport some sort of bandage. At the farmhouse, they are even more shocked to discover a drifter named Emily (Mariclare Costello) has been squatting in their home.

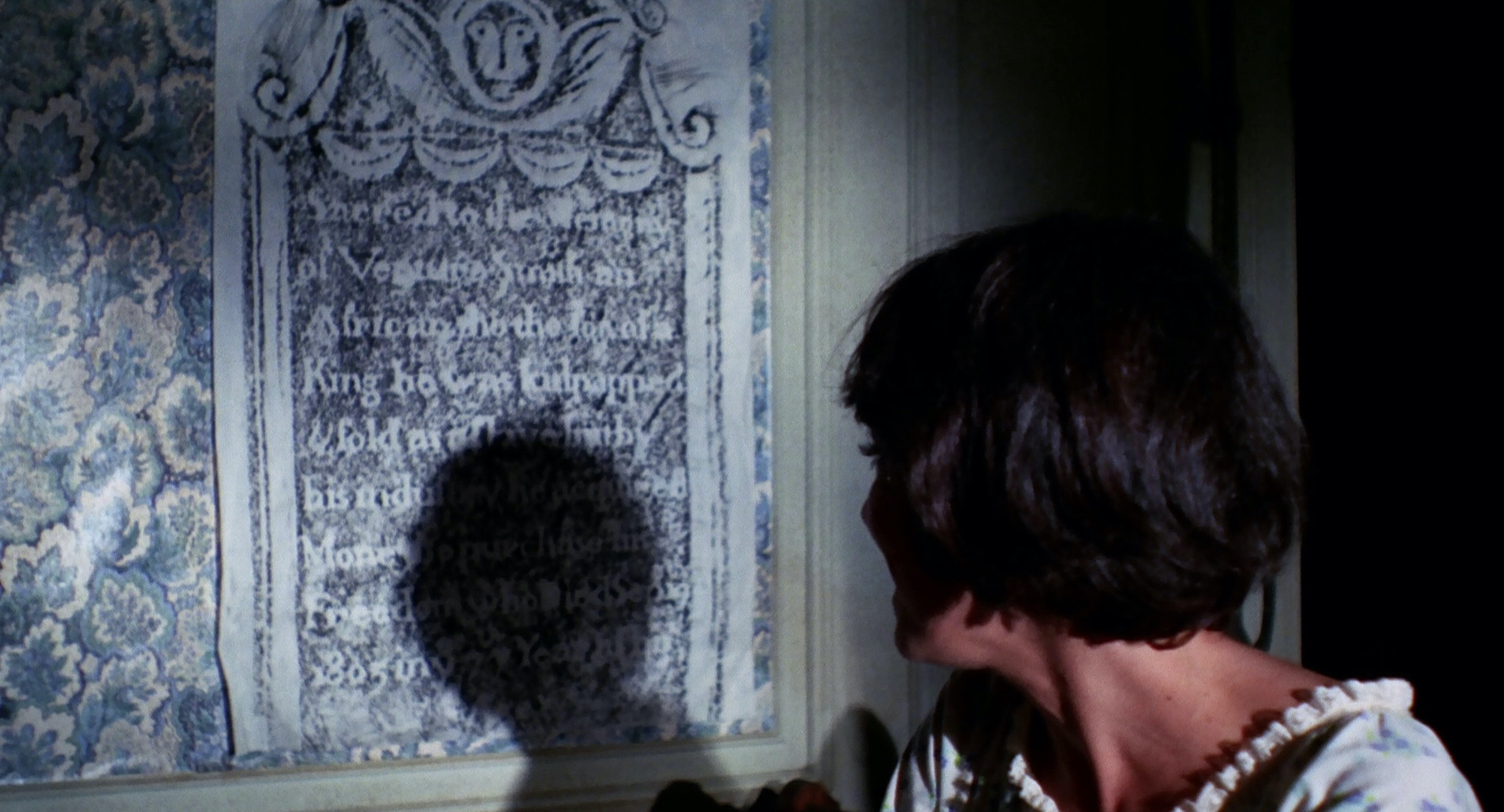

The friends invite Emily to stay on, as she seems friendly. Jessica begins to hear voices, feels someone grabbing her underwater, and sees a mysterious woman dressed in white. She is reticent to share these things with her husband, unsure if she is imagining them (which means relapsing into her mental illness and being sent “away” again) or if they are, in fact, in danger. While exploring their new house, Jessica finds an image of the home’s original owners and realizes that Emily bears a striking resemblance to the couple’s daughter, Abigail Bishop, who drowned in 1880 and is rumored to have subsequently become a vampire.

Warning: the rest of this paragraph contains explicit spoilers for the film’s ending. Duncan tells Jessica he has decided she needs to return to the psychiatric facility. While making preparations to leave, Jessica and Emily swim in the cove. In one of the film’s best scenes, Jessica witnesses Emily emerge from the water in a wedding dress as “Abigail Bishop.” She runs to the home and barricades herself in her room to hide. When Duncan comes to her rescue, Jessica is relieved until she discovers a cut on his neck similar to that on all the other locals. Emily appears with a knife, and Jessica again flees the home, this time taking a rowboat to paddle away from the town but is held back by a corpse in the water grabbing onto the boat. After stabbing the assailant, Jessica recognizes him as her husband Duncan.

Mental illness

Jessica’s unspecified mental illness is the major source of tension in the film even though the character of (tap to reveal spoiler) Emily is shown to be a knife-weilding vampire because the audience doesn’t know whether any of the horror in this movie is actually happening or if Jessica is experiencing a relapse. This gives each of the scary scenes another layer of horror because they are bookended by the threat of mental disease and/or being institutionalized. The setting of a house foreshadows Jessica’s unreliable mind as the “setting” of the movie as houses are often seen in dreams or used in art to represent our inner selves. Additionally, bodies of water symbolize our subconscious, and the pivotal scene where Emily emerges from the water as Abigail Bishop can be interpreted as confirming that the character isn’t real but represents Jessica’s unconscious rage at her husband for institutionalizing her.

Is Emily an imaginative projection of Jessica’s murderous feelings toward her husband? Of Jessica’s frustration with a mental condition that has rendered her sadly dependent on men? The film never makes clear.

Nancy West, On Celluloid Carmillas

On the other hand, the audience is also never shown any proof that Jessica is, or was ever, insane. In the opening, Duncan explains that Jessica was in a mental hospital because she had a nervous breakdown after her father’s death, but it’s understandable to go through a period of intense emotions after a parent’s death. Because Duncan provides no details other than his characterization “breakdown,” we don’t know whether Jessica’s actions were appropriate given the upsetting situation or whether they actually warranted such an extreme intervention. Duncan holds an enormous amount of power over Jessica, as he has isolated her and created a living situation where he alone is the arbiter of her reality. For Jessica, disagreeing with her husband (whether he is right or wrong) will result in her losing her freedom. Emily also presents a threat, as she moves from shy interloper to overtly flirting with Duncan. The eeriness here is the unspoken knowledge that Duncan could have Jessica committed if he decides he prefers Emily.

Her relationship with her husband is genuinely fascinating, as he quits his job as a successful musician and moves her to a secluded home where the only friend she has access to is a mutual acquaintance of theirs. As many of us now know, one indicator of an abusive relationship is a partner that fosters dependence from the other person and isolates them, effectively cutting them off from any possibility of a support network. Typically, Jessica blames herself for what Duncan has sacrificed for her and believes it is her own inability to cope that has caused his sexual interest in the young, supposedly free Emily.

Sara Century, Deep Cuts: Let’s Scare Jessica to Death

The death of counterculture

As you may have noticed from the plot summary, the film’s title is a bit nonsensical. The script was originally written as a satire by Lee Kalcheim with the title It Drinks Hippie Blood. Director John Hancock rewrote the script with Kalcheim to make it a serious and scary film. Hancock’s chosen title, Jessica, was rejected and despite not describing the actual film very well, Let’s Scare Jessica to Death was chosen instead.

Hancock has said that the film’s pessimistic mood was influenced by the cultural context of hippie counterculture giving way to 70s corruption and violence (Vietnam, Watergate, rising crime rates) saying, “You could already feel that negativity brewing when we were making Jessica; that things weren’t working out the way some of us had hoped and dreamed they would.”

Woody is a bit of a hippie. Some people would say that Jessica and Duncan are hippies as well but honestly, both of them seem to be more like people who desperately want other people to believe that they’re hippies as opposed to genuine members of the counterculture.

Alexandre Rothier, Horror Film Review: Let’s Scare Jessica To Death

The group’s identity as aging hippies is explicitly called out by locals when they refer to the newcomers as “hippie creeps.” Their counterculture ideals are also referenced by Woody and shown in the characterization of Emily as a drifter who is accepted by the trio as a peer as well as by the scene where the foursome bathe each other in the lake. The film opens with Jessica, Duncan, and Woody arriving in town driving a black hearse with the word “love” spray-painted onto the driver’s door — a visual depiction of 1960s counterculture postmortem — discussing their idyllic plan to leave Manhattan behind to make Jessica healthy by communal living in the country. This beginning feels optimistic to the extreme of being obviously foolish, and it comes as no surprise when the characters are overtaken by paranoia, jealousy, and vampirism.

The film ends with Jessica in a rowboat with nowhere to row. Whether she is insane or whether a vampire is after her matters less than the fact that she cannot escape from either. Alone with her fate, Jessica says, “I sit here and I can’t believe that it happened. And yet I have to believe it. Dreams or nightmares? Madness or sanity? I don’t know which is which.” Ultimately both interpretations have plenty of evidence in their favor and it is left up to each viewer to interpret Jessica’s story for themselves.

Jessica’s attempts to rebuild her life failed. The illness was too strong, the ghosts too overbearing. Her guilt over not being able to ‘act normal’ only exacerbated her awkwardness and invited the kind of self-hatred that would unravel her.

Kier-la Janisse, House of Psychotic Women: An Autobiographical Topography of Female Neurosis in Horror and Exploitation Films

Vampirism

One of the reasons for the enduring creep factor in Let’s Scare Jessica to Death is the mixing of horror sub-genres: The movie is about an unreliable narrator (the set-up will remind readers of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper), has elements of gothic horror and haunted house lore, contains a Carmilla-like vampire, and espouses present-day political commentary on the hippie movement. As with most other haunted house movies, Let’s Scare Jessica to Death is influenced by Henry James’s novella The Turn of the Screw as well as Robert Wise’s The Haunting (1963). Like in The Innocents (1963), also inspired by The Turn of the Screw, the constant presence of howling wind creates a spooky backdrop. As with The Haunting, the protagonist is a troubled young woman who hears voices. Jessica’s mental illness is portrayed through a unique and unsettling ability to “hear” the Carmilla-like character. The voice sometimes seems to belong to Emily and sometimes to Jessica — as we see when the voice taunts “you’ll never get better.”

There really were cases of alleged vampirism in Connecticut. Folklorist Michael Bell discusses three of them in his excellent book Food for the Dead: On the Trail of New England’s Vampires (2001). They weren’t the seductive sexual predators we see in movies, but rather were victims of tuberculosis who died. When their relatives also became sick, they thought the recently deceased person was feeding on them after death. The only way to stop the ‘vampire’ from feeding was to unearth the corpse and burn its heart. It sounds unbelievable, but Bell has evidence that the practice continued up until the 1890s.

Peter Muise, New England Folklore

Fun facts about Let’s Scare Jessica to Death

- Roger Greenspun’s New York Times review called Let’s Scare Jessica to Death “The thinking man’s vampire movie.” In another notable review, Sara Century accurately placed David Lynch films in the lineage of Jessica: “While the response is entirely subjective and it isn’t a film for everyone, Jessica did in many ways serve as a forerunner for what would come later, as filmmakers like David Lynch would delve into dreamscapes that refused to sustain themselves explicitly in cohesive narratives.”

- The antique dealer tells Jessica the lampshade she is pawning is called a “malefiori,” which is Italian for “flowers of evil.” The lampshade is actually called a “millefiori,” which just means “1,000 flowers.”

- At one point, Zohra Lampert hid in a car and refused to film the scene where she holds her murdered pet mole, because the idea horrified her so much.

- The “mole” was actually a mouse, because the crew couldn’t find a mole.

- Orville Stoeber’s score for the film was one of the first horror movies to use synthesizer music, which became the standard soundtrack for slasher films in the 80s. Shout! Factory’s Blu-ray release of the film includes a commentary with director John Hancock and producer Bill Badalato and a short interview with Stoeber titled “Art Saved My Life.”

- Some theaters gave viewers fake plastic vampire teeth at showings of the movie.

- This was John Hancock’s feature debut.