M. Night Shyamalan’s ‘Old’ (2021), Explained

M. Night Shyamalan’s Old is a thought-provoking thriller about aging and biological beings spiritual role in a world increasingly dictated by cold, scientific calculation.

Table of Contents

Analysis/Summary

Old was the most provocative horror film of 2021 because due to its horror realism. It’s a scary movie because virtually everything that happens in the plot will happen to you.

Obviously, the plot’s supernatural premise is far-fetched. A suspension of disbelief is needed to accept that there is a tropical yet creepy beach where a rare mix of minerals and magnetic charges makes you age one year every 30 minutes.

Still, the villains in Old are real, and the villains aren’t even really villains, just universal facts of life. Whether we are poor or rich, from Copenhagen or Nairobi, born in 800 or 1950, what haunts Old haunts all of us across geography, time, and social status.

This article analyzes Old as a film with two primary messages. Old is first and foremost an ode to the power of familial love inspired by filmmaker M. Night Shyamalan’s own experience watching his children and parents age, secondly, Old is a cryptic commentary on long-standing questions of when do the ends justify the means but in a way distinctively unique to bioethics at the beginning of the 2020s.

Warning: Spoilers abound. Go watch the film before reading this.

Theme #1: Love and Death

The first villain is biological aging, or to be precise, the first villain is the truism we often utter to ourselves: Where did the time go?

The Cappa family arrives on a beautiful beach. The mom and dad are middle-aged and have two children: their eleven-year-old daughter Maddox and their six-year-old son Trent. By the end of the movie, Maddox and Trent are both middle-aged and have watched their parents die of old age on the beach. Only a day has elapsed, but because of the special conditions of the beach, they witnessed almost fifty years of time in less than 24 hours.

Because Shyamalan set his script on a family vacation, the family’s rapid aging has a special emotional resonance. Viewers are left to with the sense that their rapid aging doesn’t feel unnatural; it feels like a painfully realistic reminder that soon everyone we know will be dead.

Hollywood movies often accelerate aging (e.g., Moonlight and Citizen Kane), and audiences easily accept decades flying by. Shyamalan craftily uses this narrative conditioning to reinforce the realism of what is happening to his characters in Old. Their aging feels almost appropriate for a movie, like we’re watching a family take vacations throughout their life stages: while the kids are young, while they are teenagers, as 20-somethings, and finally, their last vacation as their elderly parents are about to say goodbye to the world.

The real spell of the movie comes only if the viewer can watch the characters’ violently quick aging and at the same time reflect on their own rapid aging, with the film perhaps invoking flashbacks of the viewer’s own vacations over the decades. The older you are, the more likely you are to think the horrifying thought — the characters in this film are aging a year every 30 minutes, but I feel like my whole life has passed me by in a mere blink of the eye.

Reading the beach not as paranormal fiction but as a realistic metaphor for the stages we as humans must all go through, Old glistens with insights, life lessons, and pathos about the preciousness of life and family. To read the film this way is not an overly creative interpretation of the film. It is the explicit intention.

The movie’s opening scene features nothing but dialogue about time and aging. Trent, the youngest child, babbles, “When will get there? It’s technically been more than five minutes….Will this place have scuba diving? How old does a child need to be to do scuba diving?” The daughter, Maddox, sings a song about the inevitability of death. Meanwhile, her mother says she can’t wait to hear her daughter’s voice when she is older while contradicting herself and saying they all need to live in the moment.

The song Maddox is singing is a key to understanding the film. Interestingly, the song was written by Shyamalan’s own daughter, the recording artist Saleka, and it was made specifically for the soundtrack of Old after she read her father’s screenplay. The lyrics of “Remain” are a perfect encapsulation of what this movie is about:

But Cupid’s an archer

His violent departure

Leaves us at the altar

Wounded, weak, and ready to bleedI’ll wash away some day

No monuments made in my name

There is no life I’d trade

You were my reason to remain

And I will remain

Through comfort and pain

Till I wash awayYou are all that I can see

Alone I’m obsolete

Evеry fight is purgatoryStripped of the armor

We plеad and we barter

We stray from our harbor

Searching for some false remedy

This is a horror movie about time, the purgatory of the fact that love, however strong, is still transitory. Or in the beautiful words of Saleka’s song: “Wounded, weak, and ready to bleed…We plead and we barter…Searching for some false remedy…Until [we] wash away.”

The villains in horror movies, whether scary ghosts or crazy serial killers, offer us a safe distance from the horror. The horror of Old is real for all of us. The Cappa family’s situation — stuck, unable to stop their bodies from decaying, and losing each other to death — is our fate, too.

At the end of the film, Maddox and Trent’s father Guy remarks to his wife: “I can’t remember. Why did we want to leave this beach?” It’s a chilling line that mimics his wife’s earlier comment that everyone needs to “stop wishing away this moment.” Its dramatic effect is intensified because in our modern world it seems we’re all too consumed in anxiety to realize that however fleeting our time here on Earth, it’s beautiful, and we often don’t realize that until it’s too late.

Theme #2: Science and Soulfulness

The other villain in Old is scientism or rationalism run amok.

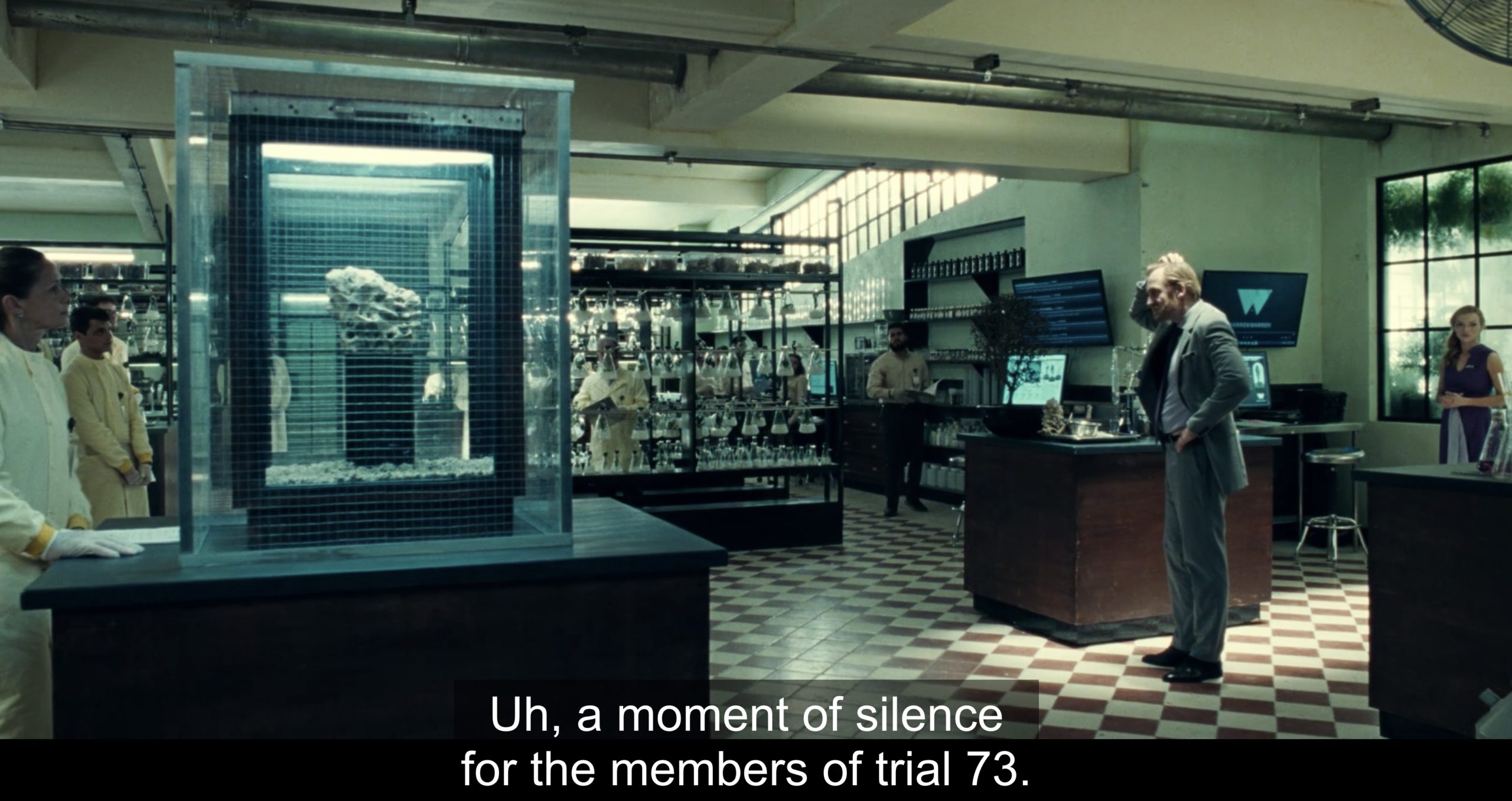

The twist in Old is that everyone on the beach was chosen by a biotech company called Warren & Warren (an allusion to Johnson & Johnson?) for medical experimentation.

Shyamalan’s real twist ending — which many viewers and critics alike miss — is that the scientist’s medical experiments aren’t evil, at least from a purely rational and utilitarian ethical code. Warren & Warren has killed about 1,000 people and saved 100,000 lives so far. And the result of their latest experiment? They just cured epilepsy.

Shyamalan’s nuance as a filmmaker shines here because he leaves open the question of how “evil” the Warren & Warren scientists are to the person watching the film; his portrayal of the scientists is agnostic and neutralized, and this provokes many uncomfortable questions.

What if Warren & Warren was real? What if their experiments could stop a pandemic or cure cancer? Would the ends justify the means? Putting yourself at the center of these questions is what makes the film truly horrifying, particularly given the historical context of Old being filmed in 2020 and released in 2021.

If you had the power and capability of the Warren & Warren team, would you sacrifice 1,000 people if it meant saving not only your loved ones from crippling and deadly disease but perhaps the whole world? Is it bittersweet that Trent and Maddox escaped and stopped the experimentation? How many people will now die because Warren & Warren was shut down?

By the mere fact that Old is first and foremost a movie about family and love, Shyamalan is making an argument against pure utilitarianism. We don’t relate with Warren & Warren, despite how good their work for society is, because it seems to violate the very essence of human rights. We relate with the human stories of those stuck on the beach. Their lived experiences — the suffering, the love, the pathos of morality — feel sacred and more important than any scientific innovation.

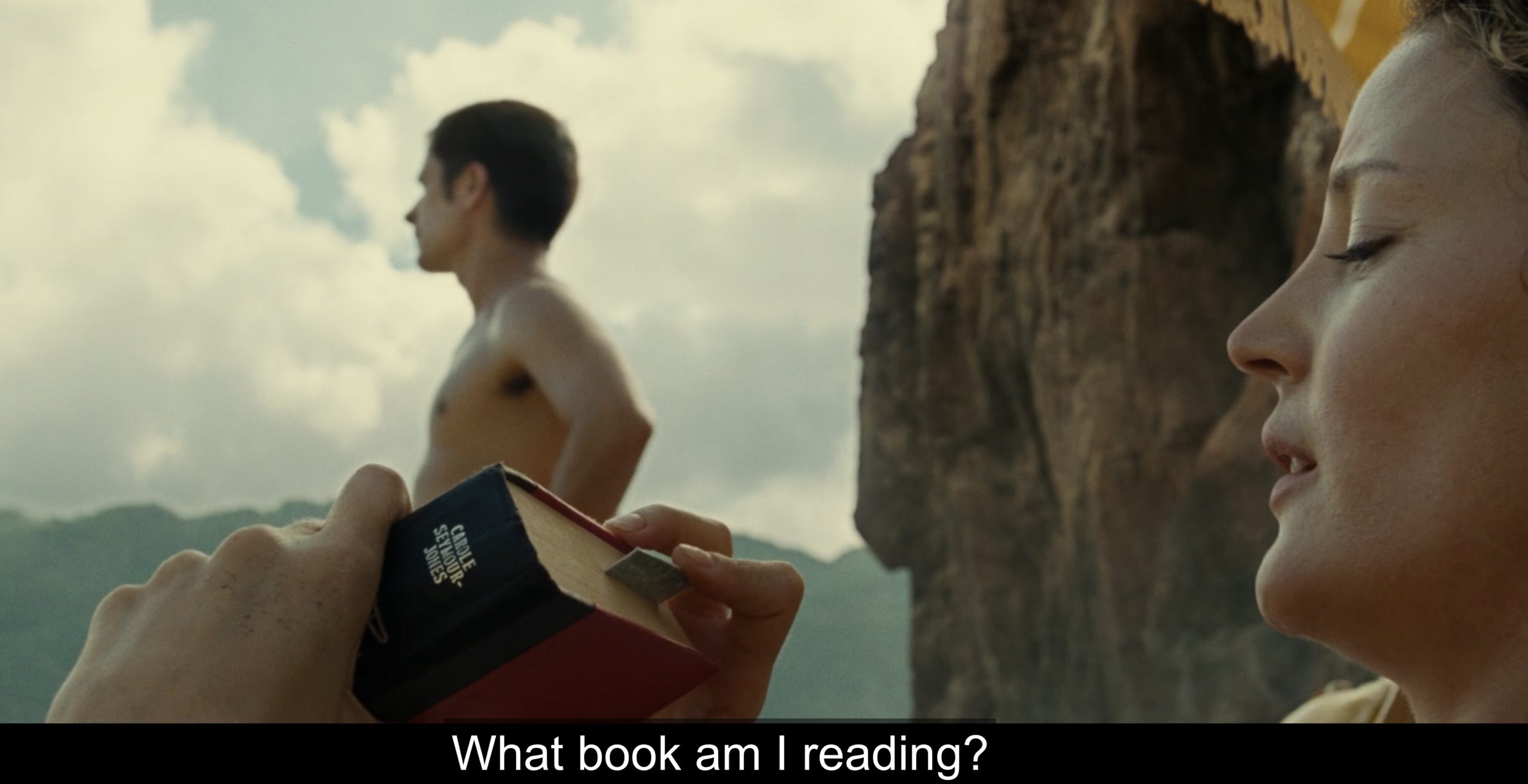

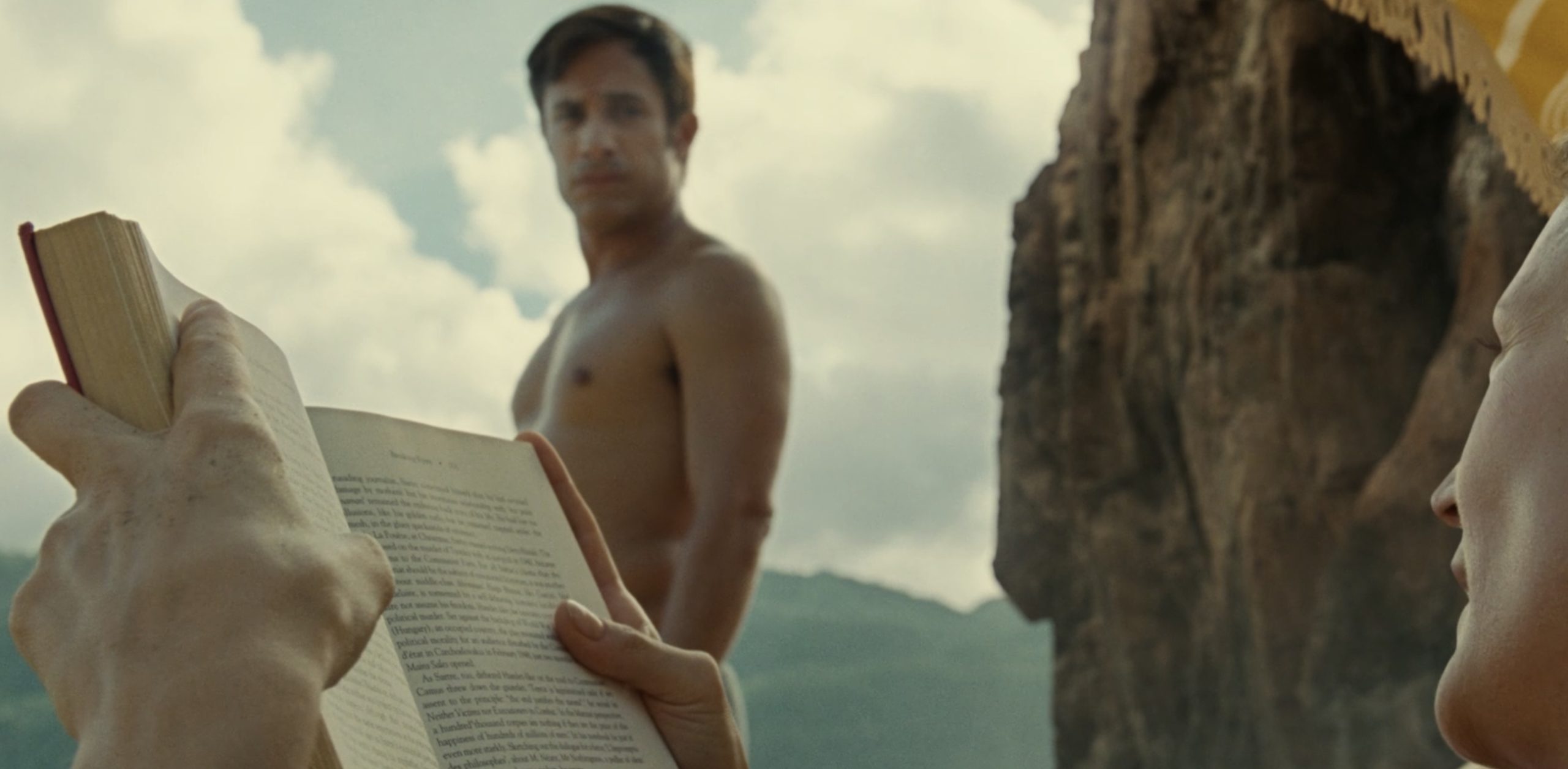

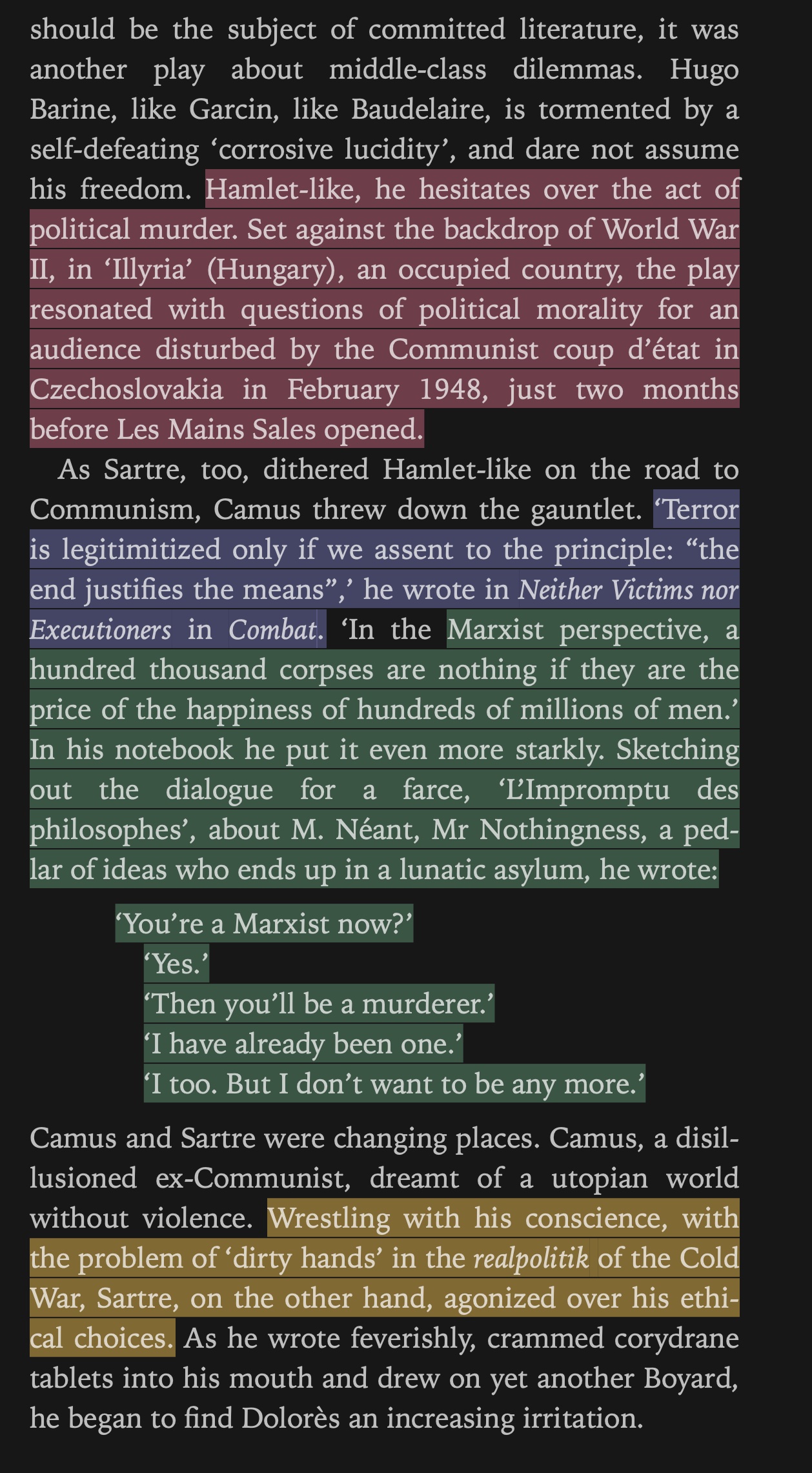

Shyamalan also hides an Easter egg on this subject. Prisca, the matriarch of the Cappa family, is reading A Dangerous Liaison by historian Carole Seymour-Jones, a highly critical biography of existential philosophers Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre.

The exact page open in the movie is about the growing drift between Sartre and his friend Albert Camus over their views on communism. Carole Seymour-Jones explains how Sartre began to justify violence in his thinking on the grounds of a higher political purpose. One excerpt from the open page reads:

Stalin’s ‘machinations’, claimed Sartre, were dictated by a desire to protect the Revolution. Violence was a ‘setback’, but an inevitable one in ‘a universe of violence’. He had taken a dangerous step towards accepting that the end justifies the means.

Further down the page, Seymour-Jones quotes Camus’s disillusion with ends-justify-the-means political philosophy:

As Sartre, too, dithered Hamlet-like on the road to Communism, Camus threw down the gauntlet. ‘Terror is legitimized only if we assent to the principle: “the end justifies the means”,’ he wrote in Neither Victims nor Executioners in Combat. ‘In the Marxist perspective, a hundred thousand corpses are nothing if they are the price of the happiness of hundreds of millions of men.’

Although Shyamalan makes the page more or less illegible, like the lyrics of “Remain”, this page subliminally cuts to the heart of what the film is about. Are hundreds of thousands of corpses fine if the price is a utopia for all of humanity? Or do we still believe there is a way toward a better society without violence? Do we only value utility, or is there something transcendent that must be respected in humanity?

Shyamalan’s answer is vague but clear enough. We know Warren & Warren from purely a statistical standpoint is ethical. Yet, still, we cheer and are happy Trent and Maddox escaped and took them down because we know there is something wrong with it. Why? The answer the film seems to provide is because when it comes to humans, there is something unique within all of us that transcends the pragmatism of science — a spirit of love, call it the preternatural, call it the soul, call it whatever you want.

Conclusion

Like virtually all time travel movies or time distortion stories, Old has plot holes, and due to the ambition of the screenplay, the film comes off at times a bit “rushed” as one Amazon reviewer ironically put it. However true this might be, Old is still a remarkable film and an important cultural artifact of the beginning of the 2020s.

When Shyamalan was asked what his favorite movies are from his canon, he listed Unbreakable (2000), Lady in the Water (2006), and Old (2021) — and any generous viewer of this movie can see why. This is a wildly original film, beautifully shot, and moving across many thought-provoking intellectual registers that are relevant to us all.