The 9 Types of Horror Movie Soundtracks

Horror soundtracks have a particular hold on filmgoers’ hearts — or, as the case may be, throats.

Film score fans will geek out on just about anything (there was even a two-disc reissue of Jerry Goldsmith’s music for Baby: Secret of the Lost Legend), but horror soundtracks have a particular hold on filmgoers’ hearts — or, as the case may be, throats.

Some scores have taken on lives of their own, regularly getting played at haunted houses or Halloween parties, while others are little recognized outside the context of the films that inspired them. Any horror fan, though, should know the classic scores that set the scene for one of today’s biggest movie genres.

Here’s a primer, sorted by category. The golden era of horror film, from the 1970s to the ’80s, is particularly well-represented here, and with good reason. Those scores are the gold standard for horror scores today, not least because the original films continue to spawn sequels and reboots where the original music themes are among the franchises’ most constant elements.

Foundational texts

Halloween (1978) and Friday the 13th (1980) defined the slasher film. While the essential setup of an inexorable killer on the loose has gone through near-infinite permutations over the past half-century, it’s rarely been done better. Like the films themselves, these scores prove that less can be more (until, of course, it’s time for a generous blood soak).

Director John Carpenter himself wrote the itchy, tinkling music for Halloween, with a sly light-footedness hinting that Michael Myers can move faster than you…much faster. For Friday the 13th, Harry Manfredini underlay eerie strings with whispered, distorted syllables. The spine-tingling effect suggests an unseen stalker, and also evokes the strobing effect of a film projector. With every frame, the killer grows closer.

Symphonic horror

An orchestra is the most conventional choice for a film score. Whether we consciously realize it or not, that sets up an expectation for how a sequence of sounds will unfurl — and the most memorable moments in orchestral horror film scores have come when composers use those expectations against us.

In scoring Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), Bernard Herrmann bent conventional tonality and cued the shower stabbing with an alarm-like series of swipes in the high strings, creating a musical meme that may (unlike Marion Crane) never die. For Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975), the masterful John Williams went low, dragging us into the depths of the ocean with a slow-building bass rumble that definitively proved a tuba can be terrifying.

More recently, as conventional orchestrations have become less common, composers have used them to pointed effect. In the score to Pearl (2022), Tyler Bates and Timothy Williams unfurl a sweeping score that harks back to the golden age of cinema. There’s an element of pastiche, but it’s also consonant with director Ti West’s old-school focus on character and motivation rather than cheap jump scares.

Fucked-up folk

A persistent trope of horror movies is the modern character caught in a community of people who hew to the old ways when it comes to human sacrifice, ceremonial sex (never as hot as it sounds), and self-immolation. This creates an opportunity for composers to delve into folk music’s more unsettling realms.

A classic in this regard is the score to The Wicker Man (1973), composed by Paul Giovanni and performed by a specially assembled group named Magnet. Twisting European folk traditions to evoke a pagan past, Giovanni and his collaborators created an uncanny blend of the festive and the frightening. The soundtrack took on its own life, cited as an influence on indie artists like Animal Collective who don’t fear the dance of death.

Bobby Krlic’s score to Ari Aster’s Midsommar (2019) is a recent touchstone in this tradition. Krlic blended electronic and orchestral sonorities with Scandinavian folk influences, while vocal artist Jessika Kenney helped to develop the chants and songs performed by the film’s fictional community of (let’s hope) seasonal slayers.

Electronic nightmares

The heyday of horror films coincided with a burst of experimentation in electronic instrumentation. While John Williams’s blockbuster success ensured that symphony orchestras would remain the film-score standard for mainstream cinema, the inhuman timbre of synthesized sound had more sticking power in the horror genre.

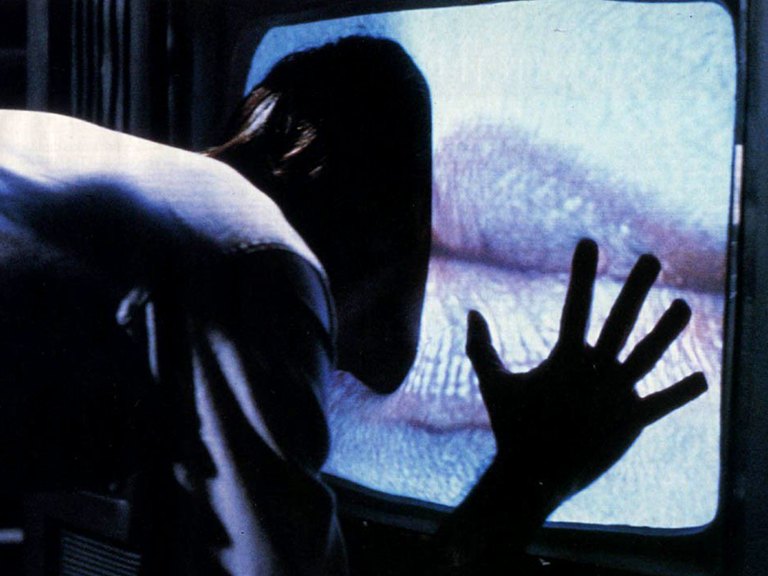

Some of the 1980s’ most evocative, while not necessarily best remembered, horror scores lean heavily on synthesized sounds. Check out Tangerine Dream’s eclectic electronic soundtrack for The Keep (1983): truly a magical mystery tour into a world of supernatural terror. For David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (also ’83), future Lord of the Rings composer Howard Shore blended acoustic and electronic sounds to evoke a deliberately disconcerting dreamscape.

Dark murmurings

Horror fans just can’t get enough stories about seemingly innocent old folks who turn out to be members of an Illuminati-style cult. These movies are also a delight for composers, who get to use the most cunning tools of their trade to sow viewers’ suspicions about that nice neighbor lady. What’s in that tea?

Nothing is wholesome in Rosemary’s Baby (1968), where a pair of gabby golden agers take the concept of “intrusive neighbor” to a whole new level. Star Mia Farrow herself sings the haunting lullaby by film composer Krzysztof Komeda, whose jazz background imbues his score with a wickedly sophisticated sensibility that fits the film’s Manhattan setting and stands out in a genre that more typically heads for night woods than nightclubs.

Colin Stetson goes for understatement in his pulsing score for Ari Aster’s Hereditary (2018), a masterpiece of dread that builds to a Grand Guignol climax under the gaze of a satanic sewing circle. After two hours of insistent gulping sounds flavored by eerily flat string tones, Stetson opens the gates of hell with a gloriously discordant fanfare for the reborn Paimon.

Minimalism for maximum discomfort

“Minimalism” isn’t a term that composers tend to embrace, but you know the sound when you hear it: dancing notes in insistent, repetitive rhythms. It can drive listeners crazy under the best of circumstances, making it a perfect fit for horror soundtracks.

The style’s first prominent appearance in the genre came with The Exorcist (1973). Forgoing an original score, director William Friedkin borrowed a handful of avant-garde classical compositions and an excerpt from Tubular Bells by the then-unknown Mike Oldfield. The album became a hit, and Oldfield’s feathery theme profoundly influenced future horror scores including, crucially, John Carpenter’s music for Halloween.

Minimalism’s household name is Philip Glass. He’s scored a wide range of movies, but in the horror genre he’s best known for Candyman (1992). Glass doesn’t just deploy his carefully parsed rhythms for flavor: the entire movie rides on his insistent signature sound. It’s also worth watching the classic Dracula (1931) with Glass’s 1999 score, composed for string quartet to fit the film’s all-too-intimate settings.

Clangs and clamor

Elegant terror, subtle rhythms, building dread…they’re all important, but sometimes you just need some good old-fashioned hullabaloo.

Prog band Goblin are here for you, and more importantly for frequent collaborator Dario Argento. Their score for Argento’s Suspiria (1977) explores the space with bass grooves, synth growls, and a jarring cascade of miscellaneous percussion. The score generally sounds like Goblin took Mike Oldfield’s tubular bells, put them in a shopping cart, and pushed it down the Exorcist steps.

David Lynch, who like John Carpenter is an auteur who helps craft his own scores, delved into ambient sound in his collaboration with sound designer Alan Splet on the score for Eraserhead (1977). A surreal soup of sound, including pre-existing music and other effects, the score pushed the boundaries of what a film soundtrack could be and underlined the disturbing onscreen imagery.

Teenage dreams/nightmares

The irreducible melodrama of adolescence is a constant inspiration to horror filmmakers, and composers have risen to the challenge with scores that hone in on that stage of life with all its identity crises, raging hormones, and oddly commonplace bloodbaths.

For Brian De Palma’s Carrie (1976), composer Pino Donaggio alternated tones of ironic melodrama, contemporary pop sensibilities, and a few spikes of screaming strings just to keep those kids on their toes. Blame Donaggio every time you let a honey-hued orchestral cue lull you into thinking an innocent teen shower scene won’t lead to buckets of blood.

It Follows (2014), one of the most satisfying teen horror films of recent years, boasted a state-of-the-art score by Richard Vreeland: the composer who works under the name Disasterpeace. With his knack for blending industrial percussion and nostalgia-tinged synth melodies, Vreeland built on the legacy of Tangerine Dream while anticipating the blockbuster success of the Stranger Things score by Kyle Dixon and Michael Stein.

Today’s game changers

What makes horror so fascinating is that it only works as long as creators keep you guessing. Blending familiarity and innovation is often the ticket to catching the eyes and ears (and other various extremities) of a new generation.

Jordan Peele is a filmmaker of singular imagination and impact, not least in his movies’ soundtracks. All are stellar, but his biggest impact on the sound of horror films came with Us (2019). A dark remix of Luniz’s 1995 hit “I Got 5 On It” was so well received in an early trailer, Peele put the remix in the movie itself alongside the original, where it’s effectively integrated with Michael Abels’s score. Since then, moody remixes of well-known songs have become positively ubiquitous.

Prey (2022) brought new life to the ailing Predator franchise, and proved a breath of fresh air for genre filmmaking generally. Sarah Schachner’s score incorporated flute and vocals by Pueblo musician Robert Mirabal, supporting the fierce film about a Comanche woman who single-handedly takes on the kind of creature who defied Arnold Schwarzenegger, Carl Weathers, and Jesse Ventura working as a team. And the 18th century Comanche didn’t even have grenade launchers.

Further reading: